Hour 15:30

29 Jan 26

The mirror, in the traditional culture of Iran, was among the objects beloved by the people. At the beginning of every task, the mirror had to be included. For example, when purchasing the bride’s belongings, the groom was required to buy a mirror before anything else; and during the bride’s procession (taking the bride to the groom’s house), the mirror had to be carried in front of the bride. Likewise, when moving into a new home, the mirror and the Qur’an had to be taken first—with the mirror even preceding the Qur’an, as it was believed to bring light. At the beginning of each month and upon sighting the new moon, people would look into a mirror. At the Haft-Seen table of Nowruz, a mirror was indispensable, and in every room or above every fireplace, a mirror was placed as adornment.

From roughly around the period contemporary with the Sassanian era in Iran, a silver-framed mirror has survived. Its glass part is missing, but the back of the frame bears the engraving of a duck, surrounded by an arabesque design.

Caption: The back of a silver mirror from the Sassanian period

Much later, Iranian artists invented mirrorwork as a means of architectural decoration—or perhaps they learned it from the people of another land. Over time, mirrorwork or mirror-mosaic became a decorative craft used in adorning buildings, ceilings, and the inner structures of temples, palaces, and the houses of kings and nobles. Craftsmen would cut the surface of large mirrors into precise geometric shapes and attach them to plasterwork, as well as into the niches and gaps of vaults and walls.

In definition, “the art of creating orderly forms in diverse patterns, using small and large pieces of mirror to decorate the interior surfaces of buildings” is called āyeneh-kāri (mirrorwork). The result of this art is the creation of a radiant and glittering space, produced by the repeated reflection of light across countless fragments of mirror.

According to the evidence at hand, it seems that mirrors were first used in the decoration of a building during the construction of the Divan-khaneh (Audience Hall) of Shah Tahmasb of the Safavid dynasty, in Qazvin. Knowing that the construction of the Qazvin Divan-khaneh began in 951 AH / 1545 CE and was completed in 965 AH / 1556 CE, one can conclude that the use of mirrors in architecture dates back at least to the mid-10th century AH (16th century CE). The use of mirrors in buildings, which began in Qazvin, spread further after the capital was moved from Qazvin to Isfahan in 1007 AH / 1599 CE. From there, it expanded to other cities of Iran such as Ashraf (today’s Behshahr), and mirror decoration was employed in the ornamentation of many Safavid palaces. Among them, the palace known as Ayeneh-khaneh (“Mirror Hall”), famous for its extensive use of mirrors in decoration, held a special place.

During the Qajar period, the mirror was regarded as a luxury object, one of the most beloved possessions of Iranians—particularly the nobles and elites—who took pride in collecting as many as possible in their homes. Mirrorwork in palaces, and gradually in the houses of the wealthy and aristocrats, became highly fashionable. So much so that the newspaper Vaqaye’-e Etefaghieh reported on 23 Shawwal 1267 AH / 21 August 1851 CE:

“The royal building within the citadel of the capital Tehran has for some time been under repair, and some rooms are being newly constructed. In most of the rooms, skilled masters—painters, plaster carvers, and glass cutters—are busy with painting and mirror-setting, producing works of great beauty and refinement.”

After the Sahebqaraniyeh Palace was built in the thirtieth year of Naser al-Din Shah’s reign, the idea of using mirrors gradually took shape in the mind of the king and his court officials. However, until 1311 AH / 1894 CE, the main hall of the Sahebqaraniyeh Palace—designed in the form of a cruciform (cross-shaped) plan, with large orsi (sash) windows facing north and other windows facing south—remained a simple hall decorated only with patterned foreign wallpaper.

Caption: The original appearance of the Sahebqaraniyeh Hall before the installation of mirrors and later alterations. The ceiling of the hall was wooden, its floor paved with stone, and its walls covered with elegant European wallpaper.

In that same year (1311 AH / 1894 CE), ten to twenty large mirrors were installed, with smaller mirrors fitted above and below them. At the same time as the installation of these mirrors, the wall coverings were also changed, and stone plinths were placed along the lower parts of the walls.

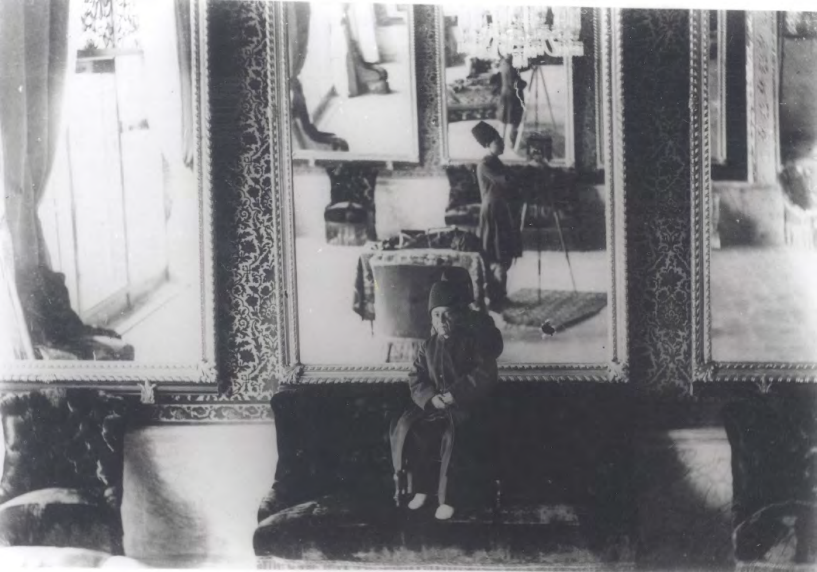

Caption: The Hall of Mirrors (Talār-e Āyeneh) of the Sahebqaraniyeh Palace in 1312 AH / 1894 CE. In this photograph, the installation of large mirror panes on the walls, the change in wall coverings, and the addition of stone plinths can be observed. Beneath the photo is inscribed: “This is Aqa Mohammad Khan (the eunuch), whose image was captured in the Sahebqaraniyeh Hall in the month of Muharram, 1312 AH / July 1894 CE.”

From that time onward, the hall became known as the “World-Reflecting Mirror Hall” (Talār-e Jahānnemā-ye Āyeneh) or simply the “Hall of Mirrors.” Its function was to host “official receptions and New Year ceremonies of salām (royal greetings).”

The mirror was a valuable object, since it was not produced in Iran and had to be imported from Europe. The finest were the fully finished Parisian mirrors, followed in order of quality by Russian and Belgian ones. For large mirror panes to arrive intact from Europe, extraordinary care along with great expense was required. If a mirror broke during transport, its fragments were repurposed in mirrorwork decoration.

Logically, the more the walls of a building were covered with large mirrors—meant to display wealth and grandeur—the greater the amount of breakage and shards produced. Thus, a use had to be found for these fragments. Qajar artists first decided to employ mirrorwork to cover the junction between the walls and the ceiling. This was executed with utmost delicacy and beauty, but it did not stop there: gradually, the decoration encompassed nearly the entire hall.

Caption: The main hall of the Sahebqaraniyeh Palace, showing the large mirrors mounted on the walls as well as the mirrorwork applied at the junction of the walls and ceiling.

It appears that the final work carried out by Naser al-Din Shah in the Sahebqaraniyeh Palace was the mirrorwork of this hall, completed two years before his assassination. E‘temad al-Saltaneh, one of the trusted courtiers and close associates of Naser al-Din Shah, writes about it:

“Today His Majesty entered Sahebqaraniyeh. In the morning, I went to Toulouzān’s house and had lunch with him. In the Sahebqaraniyeh Hall they have installed ten to twenty large mirrors, and above and below them, smaller beveled (gilāvī / gilū’i) mirrors have been placed. It is not bad at all. The Shah arrived in the hall and greatly praised his own taste, saying that he himself had ordered this style of mirrorwork.”

Caption: Mohammad Hasan Khan E‘temad al-Saltaneh

This ornamentation, which began in royal palaces, eventually extended to shrines and holy places, where wealthy patrons and nobles would sponsor sections of it as acts of offering. The only exceptions were mosques, which were exempt from such decoration, since mirrors in front of the worshipper were considered forbidden. The reason was twofold: on the one hand, their sparkle could distract the worshipper and disrupt inner presence; on the other, instead of bowing before God, one might appear to be bowing before one’s own reflection—a form of blasphemy.

One of the historical anecdotes related to mirrorwork during the reign of Naser al-Din Shah is the story of the mirror-decorated tomb of Jeyrān, the Shah’s beloved consort. The Shah ordered it to be adorned as a symbol of his own “broken mirror” after the death of his darling. Jeyrān was his only true love. The one among hundreds of women who alone had captured the wandering heart of the king. Yet this cherished companion, in the spring of her youth, fell victim to the jealousy of her rivals—the Shah’s other favoured wives—and was poisoned, leaving the monarch in deep mourning.

To soothe his grief and compensate for his loss, the Shah commanded the construction of a mausoleum for her between the shrine of Ḥazrat ‘Abd al-‘Azīm and Imamzadeh Ḥamzeh, exquisitely built and embellished with mirrorwork. But as whispers spread among the people that the Shah had placed a woman above the two revered saints, he undertook the mirror decoration of the shrine of Ḥazrat ‘Abd al-‘Azīm as well. The connecting passageway between the two sanctuaries was also adorned with superb plasterwork of flowers and birds which was an innovation in the art of plaster carving from that very era. These plasterworks remained in place until nearly the end of Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi’s reign, after which they were dismantled and replaced with mirrorwork.