Hour 16:01

29 Jan 26

Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, the second King of the Pahlavi dynasty, ascended the throne after the abdication of his father, Reza Shah, which took place at the recommendation of the Allies—particularly the British government—and with internal pressures. During his lifetime, he married three times: first to Princess Fawzia Fuad of Egypt, daughter of King Fuad I; second to Soraya Esfandiary, a descendant of Esfandiar Khan Sardar As’ad Bakhtiari, chief of the Bakhtiari tribe during the reign of Mozaffar al-Din Shah Qajar; and third to Farah Diba, granddaughter of Mehdi Khan Shoa al-Dowleh, an influential statesman of the Qajar era in Azerbaijan.

In the early years of Mohammad Reza Shah’s reign, his first two wives and his family resided in the Marble Palace and the Saadabad Palace. During this period, the royal family spent winters at the Marble Palace in central Tehran and summers in Saadabad. The Niavaran garden—especially the Sahebqaraniyeh Palace—remained a venue for hosting distinguished guests such as King Abdullah of Jordan, King Mohammed Zahir Shah of Afghanistan, and King Saud of Saudi Arabia. It was also the site of oil negotiations involving William Averell Harriman, advisor to the U.S. president, and Lord Richard Stokes, Lord Privy Seal and member of the British cabinet.

Fawzia complained about the modesty of the Marble and Saadabad palaces. Before coming to Iran, she had lived in the magnificent palaces and gardens of the Egyptian monarchs, accustomed to their grandeur. Compared to those, the Iranian palaces seemed limited and modest. Soraya, meanwhile, longed for a Western lifestyle and wealthy high-society circles, declaring that the atmosphere of Marmar and Saadabad was “repulsive.” She remarked: “The furniture is mismatched and old, the kitchens are outdated,” and lamented the absence of “Parisian décor.”

Although Soraya attempted to renovate the palaces, it soon became clear that the cost of restoration would exceed that of constructing a new palace. As a result, plans were made to build a new modern residence in the Niavaran garden, distinct from Marmar and Saadabad. At that time, however, the palace was not intended as a permanent residence for the royal family but rather as a modern venue to host the increasing number of foreign dignitaries aligned with Pahlavi’s pro-Western policies. Apparently, in 1968, while still under construction, the palace briefly served to host official guests. As Amir Asadollah Alam, Minister of the Court, wrote in his diary on January 10, 1968:

“Today, [Sheikh Sabah al-Salem al-Sabah] the Emir of Kuwait arrived. He will be our guest for five days. Tonight, a state banquet was held at the Niavaran Palace in his honour, and it was well organized. The weather was bitterly cold, and the poor Arabs were shivering.”

During construction, however, the building’s function suddenly and unexpectedly changed. Several factors influenced this shift. First, on April 10, 1965, when Mohammad Reza Shah was descending the stairs of the Marble Palace to his office, a member of the Imperial Guard attempted to assassinate him. This incident exposed the insecurity of Marmar Palace to the court, security services, and secret police.

Additionally, in 1967, the Shah’s third child, Prince Alireza, was born. According to Farah Diba:

“The birth of Alireza made us seriously think of changing homes. The Private Palace (opposite the Marmar Palace), where we had lived since our marriage, no longer accommodated us. It had only two bedrooms: one for the Shah and one for me. Reza was housed in a small annex. When Farahnaz was born, we had to add a floor to this annex. But after Alireza’s birth, expansion was no longer possible. I even turned my office into his room. This was unsustainable. The space had truly become tight.”

Thus, the royal family sought a new residence. The Saadabad complex, with its 18 palaces and vast gardens, was the first option. However, it was dismissed due to the dissatisfaction expressed by both Fawzia and Soraya and because many of the Shah’s relatives—his brothers and sisters—lived there, compromising the family’s independence.

The next option was the newly built Niavaran Palace. The problem was that this palace had not been designed as a permanent royal residence. Even today, visitors notice that its structure resembles a guesthouse or hotel, with many relatively small rooms, reception halls, and quarters for maids, guards, and servants, rather than a proper royal household.

Caption: The interior of Niavaran Palace, originally designed for hosting guests rather than long-term family residence, reflects a guesthouse or hotel-like atmosphere.

According to Farah Diba:

“Since the palace walls were not insulated against heat, summers were uncomfortable.”

The heat would get trapped inside, and with no air-conditioning installed, the only solution was to open the retractable roof for ventilation.

Caption: The retractable roof of the Private Palace, the only means of ventilation.

Caption: Farah Diba and Alireza Pahlavi between the Private Palace and Ahmad Shahi Pavilion, April 1970.

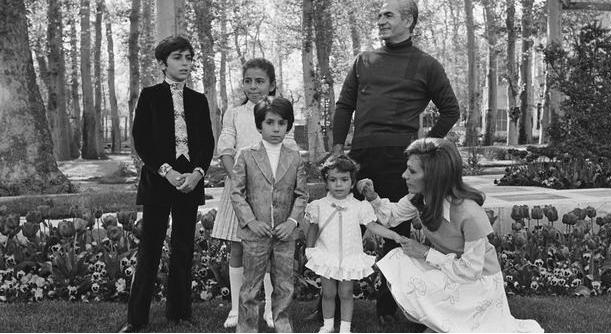

Caption: Mohammad Reza Shah, Farah, and their children at Niavaran Palace.

Despite its flaws, the new palace became the centre for Mohammad Reza Shah’s political and royal power. His relocation of the royal family from the city centre to a secluded garden could be a symbol of his increasing distance from his people.

Caption: The Shah with U.S. President Nixon and their wives.

Previously, during his conflict with Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh, the Shah had fled the country. Now, after the assassination attempt, instead of addressing the roots of public dissatisfaction, he merely changed his residence to protect himself and his family. Religious forces, centred in mosques, shrines, and bazaars, did not accompany him in this move. Real power increasingly concentrated in central Tehran, and the Shah was unaware of this—until that very power rose against him. He was used to fleeing when problems arose and eventually, after reviewing the Imperial Guard from the terrace of Niavaran Palace, he ascended the northern steps of the lawn with his wife, boarded a helicopter, and left Niavaran, Tehran, and Iran forever. He later died in Egypt.

Caption: The Shah’s last press conference at Niavaran Palace before leaving the country.

With the victory of the Islamic Revolution in 1979, the monarchy and the Pahlavi dynasty were abolished, and the palace fell into revolutionary hands. At 8 a.m. on Monday, February 12, 1979, a group of revolutionaries—accompanied by Ayatollah Seyyed Mohammad-Taqi Hakim, Imam of Hesār-e Bouali in Shemiran, along with representatives of Imam Khomeini’s welcoming committee—entered the Niavaran Palace.

Caption: The Shah’s office at Niavaran under revolutionary control.

It is said that 24 hours after the people had seized all the Pahlavi regime-related centres, Niavaran Palace remained intact, without any damage. This was because on February 11, 1979, the palace staff had raised a white flag at its entrance, declaring solidarity with the revolution. Ayatollah Hakim and six armed local youths entered the guard’s room, where Colonel Yousefinejad, the senior officer, introduced himself and declared readiness to hand over the palace, its keys, warehouses, and facilities, and provided the necessary information.

On February 12, 1979, the entire 11-hectare Niavaran complex came under local control. A list of guards was drawn up, and local volunteers replaced the Imperial Guard. Officers were disarmed, voluntarily surrendered their weapons, and were transported to their residences in Lavizan under escort.

Forty-eight hours after the seize of Nivaran Palace, on February 14, 1979, Ayatollah Haj Seyyed Hassan Mostafavi, Imam of Niavaran, was officially appointed custodian of the palace.

All palace objects and furnishings were carefully inventoried, cross-checked against royal records, and secured to prevent any loss of national property. Today, these items remain preserved within the complex, with some on display for visitors.