Hour 16:34

29 Jan 26

Reza Shah, the first monarch of the Pahlavi dynasty, ascended the throne by abolishing the Qajar dynasty with the support of Britain and at his own initiative. In the early years of his reign, he considered arranging a summer retreat for himself and his family. To this end, he took advantage of the negligence and naivete of a maternal grandson of Naser al-Din Shah Qajar and purchased from him the first parcel of the Sa‘dabad garden lands (the present-day Sa‘dabad Palace complex). Gradually, by acquiring additional parcels, he expanded the property.

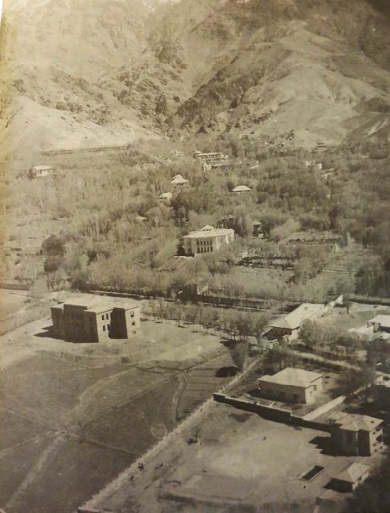

Thus, Reza Shah became the undisputed master of this entire estate at the southern foothills of the Alborz mountains and further expanded it. Today, the Sa‘dabad complex—considered the largest historical complex of Iran’s monarchical era—includes 21 palaces, of which 18 were built during the Pahlavi period. Soleiman Behboudi, a well-known figure at the Pahlavi court, writes in his memoirs:

“Little by little, His Excellency (= Reza Shah) grew fond of the Sa‘dabad garden, to the point that even outside the summer season, he would spend his Fridays there. In winters, when snow often blocked the road, they had to walk from the Tajrish bridge to Sa‘dabad, sometimes clearing the path themselves… Every year, His Majesty would move to Shemiran on June 5 and return on September 6.”

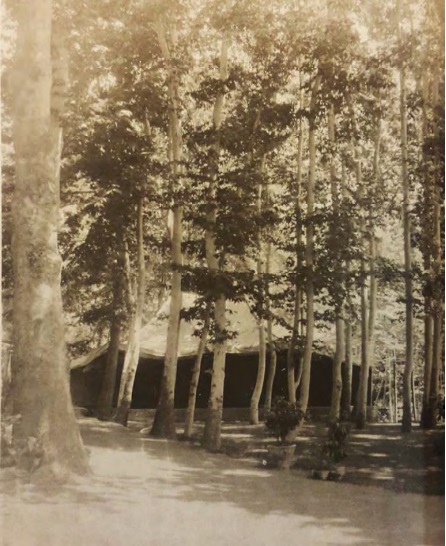

Caption: The Sa‘dabad garden in the early Pahlavi era.

It is not clear why the Niavaran gardens and summer residences did not attract Reza Shah’s attention to the same degree as Sa‘dabad, even though the district remained a beloved and popular summer retreat for Tehran’s residents. Descendants of Qajar aristocrats and nobilities—who, due to the previous residence of the Qajar kings at the Niavaran palace and gardens, had settled around it—still either lived there permanently or used their houses as summer residences during the hot months.

According to the 1949 census, published in a military survey overseen by General Razm Ara, Niavaran had a population of 670, which rose to 1,000 in summer. Interestingly, within just a few years, the population grew significantly: by the 1956 census, the village of Niavaran had 1,416 residents. This rapid growth reflects the area’s increasing importance.

Nevertheless, throughout Reza Shah’s reign, Niavaran remained relatively eventless, with limited developments taking place. By contrast, during the Qajar period, Naser al-Din Shah’s fondness for Niavaran—once the native village of his mother, Mahd-e Olya, and the site of his own wedding in youth, away from Tehran’s summer heat—had led to political and social vitality in the district. Many nobles and aristocrats, eager to reside near the king and associate themselves with the royal court, bought land in Niavaran at any price and built summer residences there. Their drive to improve the surroundings also led them to fund the construction of markets, mosques, and community spaces.

After the abolition of the Qajar monarchy, however, and specifically during Reza Shah’s reign (not that of Mohammad Reza Shah), Niavaran fell into decline. From the notes of Reza Shah’s contemporaries who remembered Niavaran’s former grandeur under the Qajars, we learn that several buildings had already vanished. Dustali Khan Mo‘ayyer al-Mamalek, a maternal grandson of Naser al-Din Shah, wrote in his memoirs:

“Now [i.e., by the late 1950s], the large outer palace [the Sahebqaraniyeh Palace] still stands, but the inner gardens and the auxiliary buildings—such as the supervisory hall, guardhouses, kitchens, and barracks—formerly located in the northern and northwestern parts of the garden, no longer exist. In the inner court, in addition to the main palace, there were once forty to fifty smaller buildings, each with four rooms and a veranda, each assigned to one of the king’s wives.”

The reason why the main palace survived may have been that Reza Shah used the Sahebqaraniyeh Palace to host visiting heads of state, such as King Amanullah Khan of Afghanistan, giving the palace a political and official function.

When the marriage of Reza Shah’s son and crown prince, Mohammad Reza, to Princess Fawzia Fuad of Egypt (sister of King Farouk) was arranged, the Sahebqaraniyeh Palace was deemed the most suitable venue for hosting both foreign and local guests. Reza Shah ordered the palace to be prepared for the wedding. All arrangements were made, and the Shah himself inspected the site and approved it. But a sudden cold in Shemiran disrupted the plan, and the wedding was held at Golestan Palace instead. The only benefit of this failed arrangement was that the Sahebqaraniyeh Palace and its furnishings were thoroughly restored.

A 1949 report describes the magnificence of Sahebqaraniyeh’s Mirror Hall:

“In Tehran, in the Golestan Palace, the Parliament, and many royal residences, there are mirror halls, but none equals the size, beauty, and grandeur of the World-Reflecting Mirror Hall of the Sahebqaraniyeh Palace. It seems as though light itself flows from its walls and mirrors, and the mirrors are made of light. At night, when the chandeliers are lit, the sight dazzles the viewer. Unlike the other chambers and basements of the Sahebqaraniyeh, which are filled with precious paintings and fine furniture, the World-Reflecting Hall is almost devoid of ornamentation, for its natural radiance surpasses all decoration.”

Caption: The Mirror Hall of the Sahebqaraniyeh Palace, probably in 1948.

To achieve this restoration, the plan was to transform the Sahebqaraniyeh into a modern and dignified palace. For eight months, day and night, teams of engineers, carpenters, painters, and electricians laboured. Notable artists such as Aqa Hossein Sheikh (a leading painter of the era) and Aqa Nejat-‘Ali (a frame-maker) worked on the site. Some priceless carpets from Golestan Palace were moved to Sahebqaraniyeh. The smaller rooms were renovated according to the latest styles, furnished with items purchased from all over the world, giving the palace a nearly mythical character.

The wall running east to west in the north of the Sahebqaraniyeh Palace, which separated the outer palace from the inner quarters of the royal harem and eunuchs (likely the same fence that still divides the two sections today), was removed during this renovation. Almost all of Naser al-Din Shah’s inner pavilions and smaller mansions were demolished, leaving no trace today of what were once forty to fifty separate residences. In addition, some changes were made to the palace’s interior design, though they did not damage the building’s overall integrity, and its Qajar architectural identity remains evident. Most exterior alterations were only necessary repairs.

Among the older surviving structures is a pavilion in the northern courtyard of the Niavaran garden, now known as the Ahmad Shahi Pavilion, though its attribution to Ahmad Shah Qajar is highly questionable. Its function in earlier times remains unknown, but it is certainly among the oldest structures in the complex, if not the very oldest. Why this building was spared while so many others were destroyed is unclear. What unique quality led Reza Shah to preserve it? Its construction? Or perhaps a personal memory from Reza Shah’s distant past We cannot say.