Hour 13:30

29 Jan 26

In old Iran, the andaruni (inner quarters) of a house was a section reserved for women, and no man, except the master of the house, was permitted to enter. In the case of kings and statesmen, however, matters were somewhat different, since these men of power always enjoyed and partook of worldly blessings more than ordinary people. As they themselves would say, “woman” and “possessions” (in other words wealth and property) were among the delights of this world. Thus, they typically had multiple wives as well as treasuries full of money and goods. During the Qajar era, the king—who was the wealthiest man in the country—kept numerous women in his private retreats and andaruni, surrounded by eunuchs and maidservants, and they would spend their life in luxury and pleasure.

In earlier times, owning slaves—both female and male—was a common and socially accepted practice. Yet these slaves were often quite different from what we imagine today. The term gholam (male slave) or kaniz (female slave) may conjure images of ugly, brutish, or dull-witted individuals, but in reality, many of them were remarkable and skilful in many aspects. Some were literate, knowledgeable in the arts, proficient in music and singing, and accomplished in other necessary skills, to the extent that they were presented as gifts to rulers. The names of certain such slaves have even survived in people’s memories and in the pages of books.

The male slaves were often experts in various fields—companionship with nobles, conversation, providing entertainment during gatherings, poetry, storytelling, and reciting histories and tales. The female slaves were skilled in attending to royal women and noble ladies, as well as caring for children. Those who had not attained such skills were instead employed in tasks such as fetching water, farming, cleaning, washing, pulling carts and wagons, and other demanding or less desirable labour.

The buyers of such slaves were usually the wealthy and the statesmen, with the foremost among them being the royal courts and the kings themselves, who received the finest slaves either as gifts or by purchase. By the Qajar period, all these slaves had been absorbed into the royal andaruni. The inner court was filled with Georgian, Turkic, and Roman slaves. Nobles, governors, and grandees, following the king’s example, also ordered slaves for themselves, as possessing them was considered a mark of honour, prestige, and grandeur. The greater or lesser number of such slaves was directly tied to one’s social status and dignity. In turn, slaves became a measure of the wealth and prominence of merchants and wealthy men.

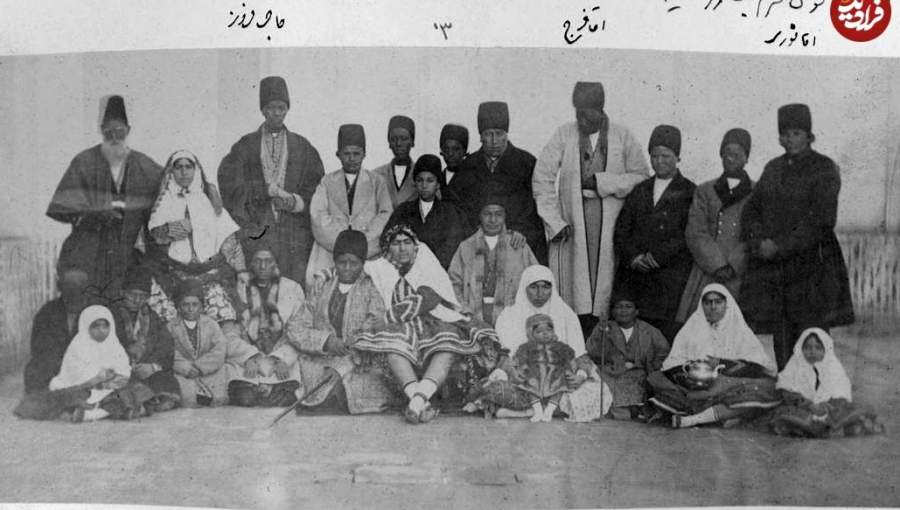

Caption: A group of servants and eunuchs of the harem surrounding young princes and noble children

During the reign of Naser al-Din Shah, in order to house the vast number of women of the royal harem along with their attendants, servants, and maids, the first Royal Retreats (Khalvat hā-ye Homāyuni) were constructed north of the Jahan-Nama Palace. These significant sections of the palace endured much longer than the Jahan-Nama building itself; for even after the demolition of Jahan-Nama, these gardens and secluded palaces continued to exist, serving as the Royal Retreats of the Sahebqaraniyeh Palace, still used as residences and leisure spaces for the secluded Qajar ladies and their guests.

Owing to the fact that these Royal Retreats enjoyed a longer historical continuity than other buildings of the Niavaran Garden complex—and since they remained intact until the period when photography was introduced to Iran—numerous fascinating photographs of these structures survive, allowing us a much clearer understanding of their condition.

From these images, we learn that the ladies of the harem, their eunuchs, and maidservants each had designated residences within the Niavaran Gardens, comprising forty separate and independent buildings, each containing at least three rooms. All the doors of these rooms opened directly toward the Niavaran Garden. Among them, one mansion was larger than the others and had a grand veranda (eyvan). In front of these forty residences, a royal hall was built, which also featured a veranda for sitting and enjoying the fresh air and pleasant scenery of the garden. Around these residences, tents were also erected either temporarily or permanently. Permanent tents were used when space within the buildings felt insufficient, while temporary tents were set up when a lady, after strolling in the garden or finishing daily tasks, wished for a secluded corner to rest on the garden’s lawn. The remaining lodgings belonged to the servants and the labourers of the inner court.

Caption: One of the Detached Buildings of the Inner Quarters of the Sahebqaraniyeh Palace

The servants and attendants of the inner court were divided into three groups:

• Orderlies and soldiers, who guarded the citadel and its surroundings;

• Maids, servants, and other staff such as sweepers, gardeners, lamplighters, water carriers, and the like, who served within the citadel;

• Black slaves and maidservants, who were responsible for safeguarding the honour of the women of the harem and ensuring that they had no contact with outsiders or unrelated men.

Caption: A group of attendants and servants of Naser al-Din Shah’s inner court

These black slaves and maidservants were men and women who had been purchased as slaves from Abyssinia and Zanzibar. The women were trained in espionage and reporting, while the men were castrated and assigned to guard the royal ladies. They were generally simple-hearted and trustworthy people, except for those few who, through bad associations, had learned corrupt habits. Most of them remained loyal to their master until the end of their lives.

The honorary title Daddeh-bashi was given to the most respected among the women, and Khajeh-bashi to the men of this group, awarded in recognition of their faithful service, honesty, and reliability. Although seemingly the duty of this group was to serve the ladies of the harem, tending to their food, cleanliness, and daily needs, in reality, however, their task was to carefully monitor and investigate the behaviour of the women: their interactions with relatives, their meetings with one another, their correspondence and letter-writing—all of which were observed in detail and reported to the eunuchs (Khajeh-bashi).

The Khajeh-bashi, acting as a supervisor with full authority, was responsible for pointing out the women’s minor indiscretions, and for informing the head matron of the harem—a senior and highly respected woman chosen from among them—about any serious misconduct. She, in turn, decided whether to report such matters to the Shah or to deal with them herself, whether through exposure, punishment, reprimand, or concealment.

This strict surveillance over the royal ladies was due to the fact that they were considered among the Shah’s most sacred possessions (nawamis-e akbar) and therefore had to remain completely veiled from any outsider. The tradition placed them in a position almost akin to that of dangerous political prisoners (!), under constant attention and scrutiny by the attendants. These restrictions and deprivations often drove many of them toward despair, and at times even death or suicide. The severity of such constraints reached its peak when very young girls who had recently been brought into the Shah’s harem wished to leave the andaruni to visit their parents or relatives, or to travel anywhere. No lady of the harem was allowed to move freely even between the buildings of the inner court unless they were dressed in a full black veil (chador), a cloak that covered their legs (chaqchur), and face covering (rubandeh), while being escorted by eunuchs and senior maidservants to clear all male staff from her path. They were not allowed to visit their parents or relatives without prior permission, and even then, only if accompanied by a trusted maidservant appointed by the Khajeh-bashi. They were also forbidden from shopping in the bazaars, except in the most secluded hours of the day, and only with several eunuchs and maidservants accompanying them, and even then, they were instructed to purchase only from shops whose sellers who were old and frail.

Caption: A group of royal harem ladies

At any rate, from the surviving writings we know that the women of the inner court (andaruni) seem to have lived more comfortably in the andaruni of the Sahebqaraniyeh Palace than in the inner quarters of other palaces in Tehran or in the provinces. One possible advantage of the Niavaran andaruni, compared to others, was its spaciousness and the fact that a large portion of the garden was reserved exclusively for the Shah’s harem.