Hour 12:10

29 Jan 26

The Niavaran Cultural and Historical Complex is one of Iran’s unique and exceptional collections. Thanks to its refreshing greenery, its habitat for numerous animal species, the remarkable architecture of its buildings, its beautiful landscapes—including views of the towering mountains above it—and its historical antiquity, it is considered a truly distinctive complex.

What is striking is that the spatial design of the complex was inspired by the natural and geological features of this region in ancient times. Even more astonishing is that, despite the grandeur of its Iranian architecture and the abundance of beauty in its structures—which have made it one of the rare and remarkable attractions of Iran—the initial encounter upon entrance never leaves one stunned, nor does it even immediately arouse much curiosity or interest.

When you step into the grounds of the historic garden from any of its entrances, at first you cannot distinguish this garden and its buildings from other aristocratic gardens and mansions of Iran’s past. In fact, a vague, suffocating sense—much like the estrangement one feels in a foreign land—seems to clutch at your heart, suppressing your eagerness to enter the palace. Yet with every step you take deeper into the complex, you become increasingly enchanted and thrilled to realize how this historical site, from the Qajar era up to the present day, has remained so magnificent and glorious.

Caption: The Pavilion Known as the Ahmad Shahi Pavilion in the Niavaran Cultural-Historical Complex

Contrary to popular belief, palaces and mansions of dignitaries were not solely intended for their private life and gatherings. In many cases, they also served as places for public interaction. Within them, public spaces were designed where people could freely gather and engage in social and communal activities, such as holding religious ceremonies. On important occasions, the king and courtiers would join the people, and the usual social distance between rich and poor would be lifted. For example, all would mourn and weep together in memory of Imam Hossein (the third Imam of the Shiʿa branch), or during births and celebrations, sweets and sugar-coated almonds would be distributed equally among both the wealthy and the poor, and at times feasts would be arranged to feed the public.

Today, visitors and tourists of the Niavaran Cultural-Historical Complex, which includes the Sahebqaraniyeh Palace, enter from the same direction as in earlier times during the Qajar dynasty, when kings, courtiers, ambassadors, and both ordinary and distinguished visitors would arrive at the summer garden and mansions of Niavaran. This entrance, located on the western side of the complex facing today’s Niavaran Square, remains the place where tickets are sold and visitors enter.

At this spot, there once stood a jolo-khān (forecourt). The jolo-khān was an “open area” that formed part of the entrance structure, situated just before the grand gateway of the complex. After crossing the forecourt, visitors to the palace would pass beneath the sardar-e ʿālī (Imperial Gateway, also known as Bāb-e Homāyuni) and enter an enclosed courtyard where guards and servants resided. From there, they would pass through a vaulted passageway (zirtāqi) and enter the Niavaran summer garden, with the northern façade of the Sahebqaraniyeh Palace facing toward it.

Based on descriptions by contemporary writers of the Qajar era, it is revealed that this forecourt and the enclosed courtyard beyond it correspond to the present-day area which is immediately after the palace entrance. The vaulted passageway also remains intact in its original form; after passing through it and a short corridor, one enters the garden toward which the northern façade of the Sahebqaraniyeh Palace still faces.

Caption: The remaining structure in the present entrance area of the palace, which is believed to be the same “Sahebqaraniyeh Forecourt” (Jolo-khān) during the Qajar era.

Caption: A small enclosed courtyard to the west of the Sahebqaraniyeh Palace, which may have been the “Sahebqaraniyeh Forecourt” (Jolo-khān) during the Qajar era.

The term jolo-khān is a compound word consisting of jolo (meaning “front, before, opposite”) and khān (meaning “residence, dwelling”). Thus, jolo-khān refers to the courtyard in front of a residence, the stage before entering the house, a preliminary threshold, or a space for preparing oneself before stepping into the residence. In practice, in Iranian domestic architecture, the jolo-khān is the foyer of the house, while in the architecture of palaces and courtly mansions, it becomes a square or open space in front of a grand building or palace. It is a transitional and connective space, marking the boundary between the exterior and the interior of the residence, and is generally enclosed on several sides. Upon entering the jolo-khān—the enclosed forecourt before the building—visitors pause in this new setting, gaining the mental and spiritual readiness to enter the inner quarters and present themselves before the homeowner or the dignitary residing in the mansion.

The main distinction of the jolo-khān from other royal spaces lies in the fact that it was considered a public space, which gave it special significance in fostering interaction between the court and ordinary citizens. Within such a space, people could meet and converse with the king and court officials more closely, while also maintaining a certain degree of freedom in their behaviour, movement, and speech, similar to their everyday life in the streets and marketplaces. At the same time, there were often common themes and occasions for gathering courtiers and townspeople in this public setting, which in turn brought hearts closer together and temporarily bridged the social gap between rich and poor.

The Sahebqaraniyeh Palace’s jolo-khān also served, over the years, as a place for religious ceremonies. A news report from 1314 AH / 1896 CE, during the reign of Mozaffar al-Din Shah, records:

“This is the royal summer court. A grand tent was erected, the preparations for the mourning ceremonies were made, and every afternoon a session of rowzeh (religious lamentation) was held… Afterwards, elaborate shabih (ritual passion plays) were staged… His Majesty would take his seat in a special chamber overlooking the stage and fully partake in the spiritual benefit of the ceremonies.”

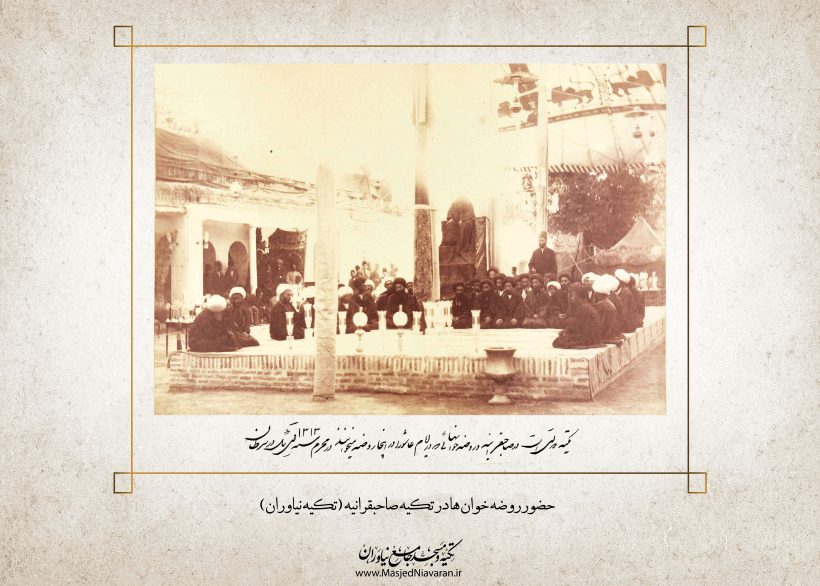

Caption: The royal tekyeh (religious mourning rituals) at Sahebqaraniyeh, where state-appointed preachers recited rowzeh (lamentations) during the days of Ashura – Muharram 1313 AH / June 1895 CE.

Another report from 1315 AH, just one year after the previous account, informs us that in the very same place, the celebration of the Prophet Muhammad’s birthday was held:

“On Monday night, the 17th of Rabiʿ al-Awwal (16 August 1897 CE), in front of the royal garden of Sahebqaraniyeh—which at this time served as the residence of the servants of His Sacred Majesty and his selected attendants—countless illuminations and fireworks were performed by order of the state.”

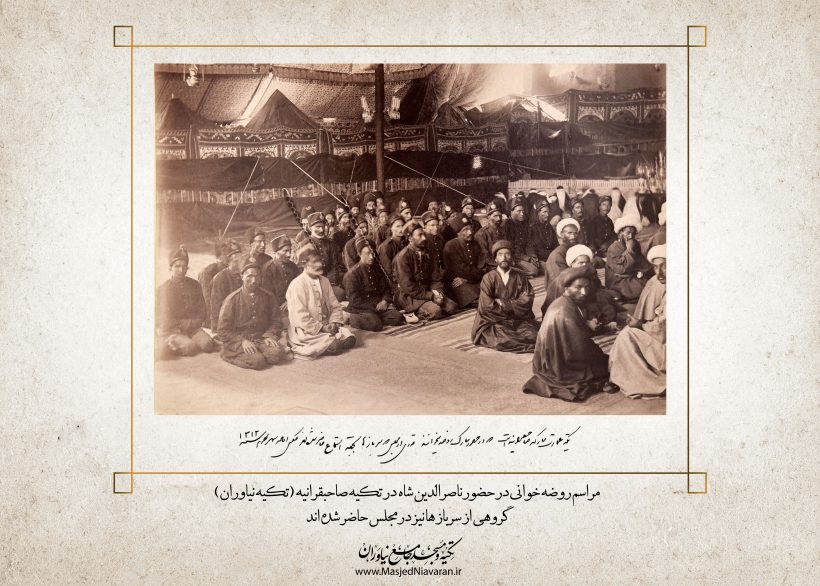

Caption: The tekyeh (mourning theatre) of the Sahebqaraniyeh Palace, where rowzeh (lamentations) were recited in the royal presence [that is, before the Shah], with a number of soldiers attending the assembly to listen – Muharram 1313 AH / June 1895 CE.

Returning to the introduction of this discussion, it should be emphasised that the mention of the jolo-khān of the Niavaran Garden and the Sahebqaraniyeh Palace carries significance because it reminds us that these seemingly simple spaces—which may not even spark a visitor’s curiosity for a moment—are in fact bearers of the historical memory of Iranians and thus call for reflection and renewed recognition.