Hour 13:59

29 Jan 26

Naser al-Din Shah Qajar ruled longer than any other Qajar king before or after him. When his reign reached thirty years, he decided to build a palace worthy of such a position among monarchs—one that would preserve his name in history and remind future generations that he had held the throne for such a long period. Thus, he ordered the construction of a palace named Sahibqaraniyeh in the Niavaran summer garden, which he had always been fond of.

The construction of the Sahibqaraniyeh Palace began at the time of the thirtieth anniversary of Naser al-Din Shah’s reign. In those days, each thirty years was called a “century,” and the name Sahibqaraniyeh clearly conveyed that meaning. Even today, this name is still applied to what remains of the palace, showing that Naser al-Din Shah succeeded in passing on the concept he had in mind.

This palace—which now only partially survives under the name Sahibqaraniyeh—once had numerous halls and various rooms, most of which served ceremonial purposes, especially for court gatherings such as the Nowruz Salam (Hello New Year).

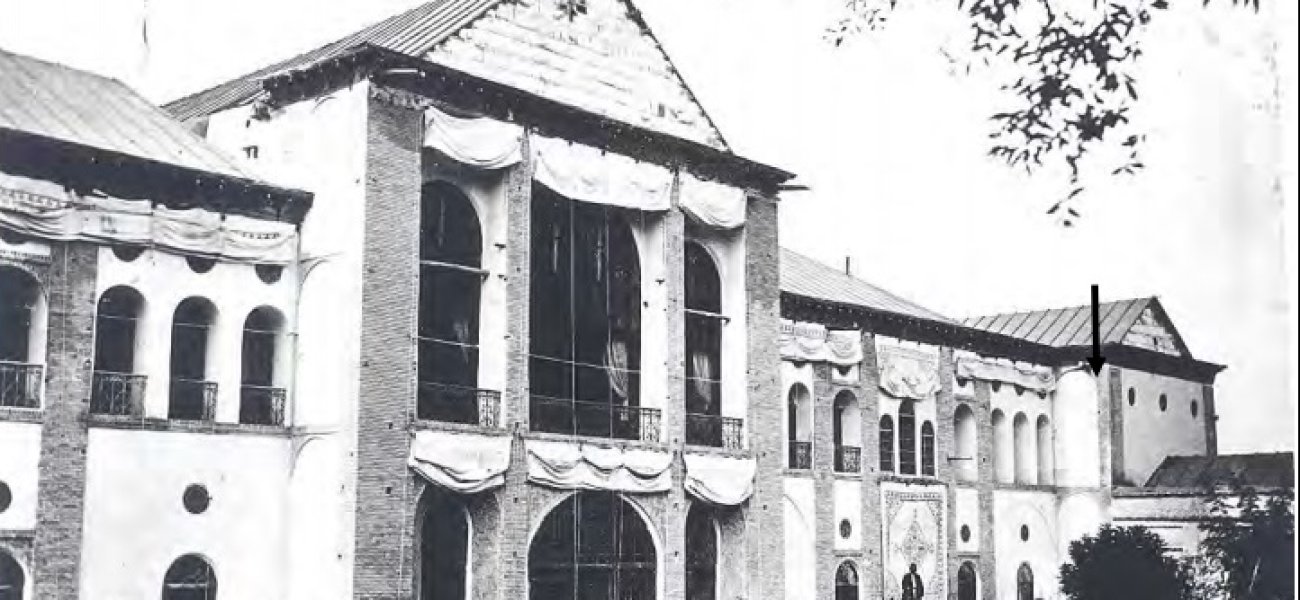

Caption: The appearance of the northern façade of the Sahibqaraniyeh Palace during the reign of Naser al-Din Shah

This, of course, is aligned with the traditional Iranian spirit and culture, in which households always had one or more rooms called the mehmān-khāneh (guest room or reception room). These rooms would remain closed to the family throughout the year, and whenever a guest arrived, the hosts would sweep and prepare the guest room and invite them inside with exceptional courtesy and reverence. They would then present all kinds of foods and drinks—dishes that the family themselves might not even see throughout the year—before the guest, insisting with great formality and persistence that the guest partake of everything on the table. The same custom prevailed in the royal palaces as well.

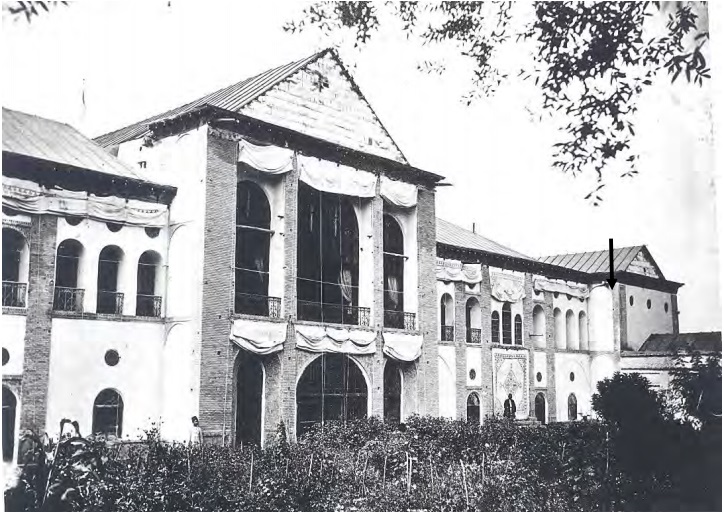

Caption: The original state of the Sahibqaraniyeh Hall before the installation of mirrors and later modifications. The ceiling of the hall was wooden, the floor was paved with stones, and the walls were covered with beautiful European wallpaper.

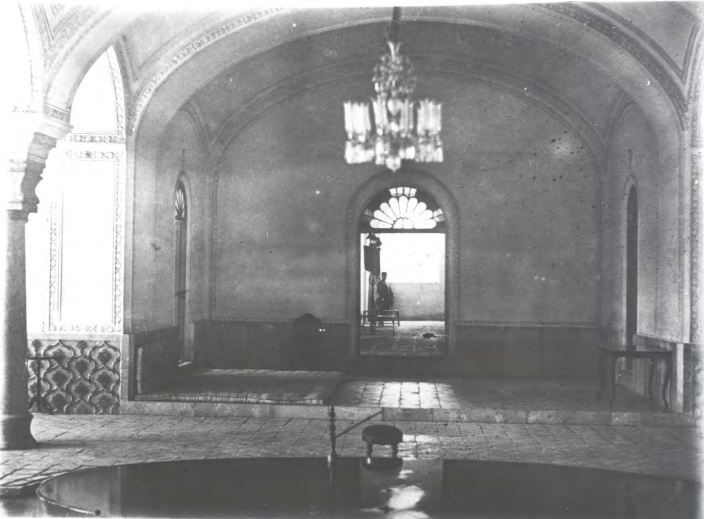

Naser al-Din Shah would usually spend his time in the cool basement of the palace, known as the Howz-khāneh (pool chamber). Several photographs exist of him in this small yet charming space, sometimes surrounded by the royal attendants and servants of the palace.

Caption: The Howz-khāneh (pool chamber) of the Sahibqaraniyeh Palace, in which Naser al-Din Shah himself can be seen at the far end of the corridor. This photograph was taken on the day of Eid al-Adha, on 10 Dhu al-Hijjah 1307 AH / July 28, 1890 CE, and it appears the Shah is preparing to attend the Eid al-Adha Salām (ceremonial audience with the Shah).

These photographs also reveal that the Shahneshin (royal sitting area) and the Takhtgāh (throne) of Naser al-Din Shah, located in the northern part of the Howz-khāneh, remain the most untouched section of the entire Sahibqaraniyeh Palace to this day. The marble throne platform and its surroundings bear a complete resemblance to their present condition.

Caption: A photograph of Naser al-Din Shah Qajar sitting on the edge of the northern Shahneshin (royal sitting area) window of the Sahibqaraniyeh Howz-khāneh (pool chamber). Beside him stand the royal attendants and servants of the palace. By comparing this image with the current state of this section of the building, it seems that this part has survived and has been preserved in its original form.

On the front wall of the Shahneshin of the Howz-khāneh, there once stood a carved image on marble depicting scenes from the story of Sheikh San‘ān, a famous story of Attar of Nishapur. Sheikh San‘ān is portrayed as a devout and experienced ascetic who falls in love with a Christian girl. The girl sets four conditions for marrying him: to bow before an idol, to burn the Qur’an, to drink wine, and to renounce his faith (Islam). Sheikh not only fulfils these conditions but also tends pigs for a year to prove his devotion to her. Eventually, when the girl sees the Sheikh’s passion and devotion, she herself falls in love with him and converts to Islam. Yet the Sheikh transcends earthly passion and frees himself from attachment to her; nevertheless, the two ultimately unite, and the tale ends happily.

The theme and content of this story carry a certain charm that explains why its imagery was carved in the Shah’s favourite resting place. This area appears to have been entirely private, as there are spaces still present today at the eastern end of the Howz-khāneh corridor that may once have served as a bath for the Shah. The water of the Howz-khāneh flowed from beneath the Shahneshin, filled the central basin, and spouted upward from the small fountain in its middle.

Caption: A painting of the Howz-khāneh in the Sahibqaraniyeh Palace and its central circular pool during the reign of Naser al-Din Shah, by Kamal al-Molk. The northern Shahneshin, which served as the Shah’s throne platform, can be seen on the right side of the painting. The space opposite it (on the left side of the canvas) is clearly set at a lower elevation compared to the Shah’s throne in the northern part of the Howz-khāneh.

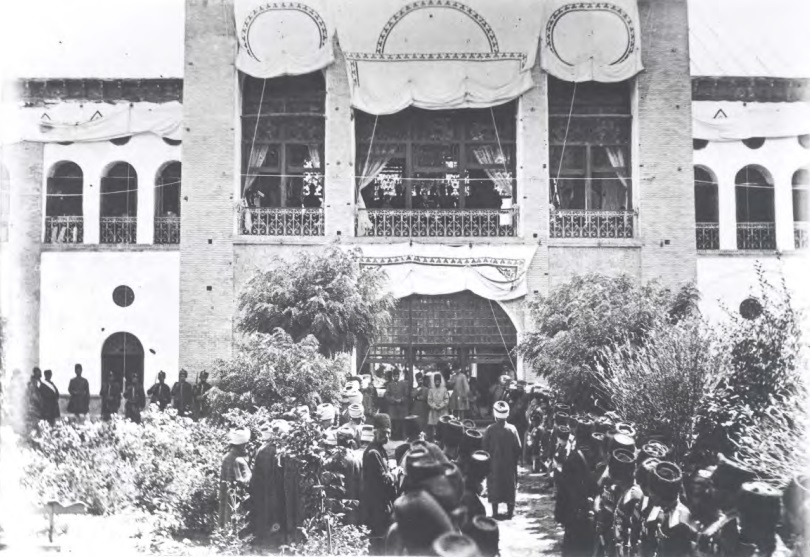

Contrary to the common belief that the Golestan Palace was Naser al-Din Shah’s principal residence, the more accurate account is that Sahibqaraniyeh was always the Shah’s favoured palace. Certain official ceremonies, such as the Salām-e Ām (public audience) as well as mourning rituals and the performance of Ta‘ziyeh (religious passion plays), were held in the Sahibqaraniyeh Palace.

Caption: The Salām ceremony of Eid al-Adha in the northern courtyard of the Sahibqaraniyeh Palace, on 10 Dhu al-Hijjah 1307 AH / July 28, 1890 CE.

In the notes of foreign ambassadors as well as Iranian contemporaries of Naser al-Din Shah, the summer garden of Niavaran and the Sahibqaraniyeh Palace were regarded as the most beautiful summer residence of the Shah. Its andarun (inner quarters) was considered one of the finest royal inner courts, where the ladies of the harem lived more comfortably and happily than in the andaruns of other palaces.

The splendour of Sahibqaraniyeh, however, seemed to vanish abruptly with the assassination of Naser al-Din Shah—who was known as the “Sultan-e Sahibqerān” (the King of the Sahibqerān). His successor, Mozaffar al-Din Shah, ascended the throne as an ailing, tubercular old man after his father’s long reign. Known for his stinginess, he ordered the women of Naser al-Din Shah’s harem, who resided in the northern wing of Sahibqaraniyeh, to take all their belongings and vacate the palace, so that he would pay less in allowances and maintenance. Consequently, the lively gatherings of the andarun, which had been so vibrant and customary in Naser al-Din Shah’s time, came to a complete end, and visits from guests ceased altogether.

After his trip to Europe, one of the curiosities that Mozaffar al-Din Shah brought back to Iran was an “incubator machine” for hatching chicks. Strangely enough, the Sahibqaraniyeh Palace was chosen as the place to install this device. According to Prince ‘Ayn al-Saltaneh:

“That beautiful, soulful, and delightful andarun of Naser al-Din Shah—which had been the centre of fashions, adornments, and festivities—in Mozaffar’s reign was turned into a dump and refuse heap, a place for feeding lambs and goats, while flocks of turkeys, geese, ducks, chickens, roosters, and pigeons roamed every corner of the courtyard pecking at grains.”

Since chicks were bred in large numbers throughout the garden, the palace, and even inside the rooms after the arrival of this “incubator machine,” the palace must have suffered serious damage and filth during this period.

And yet, with all this decline described above, how was it that such an important decree as the Constitutional Edict was signed at Sahibqaraniyeh by Mozaffar al-Din Shah on 14 Jumada al-Thani 1324 AH / August 5, 1906 CE? That, indeed, is another story to be told separately.

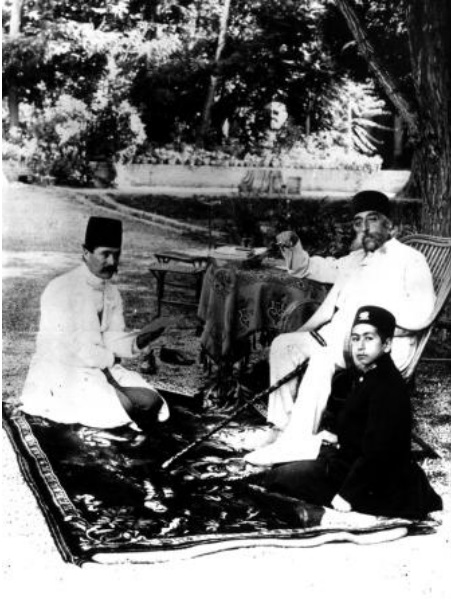

Caption: A photograph of Mozaffar al-Din Shah in the garden of the Sahibqaraniyeh Palace, believed to date to the time of the signing of the 1906 Constitution.

Thereafter, Sahibqaraniyeh continued its life into the Pahlavi era, undergoing major renovations and changes, especially during the reign of Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi. After the Islamic Revolution, great effort and care were devoted to ensuring that this palace and the neighbouring royal residences and structures would be preserved exactly as they were at the time of the Revolution. It appears that these efforts have been largely successful, for today the complex can be regarded as carefully protected and untouched, preserved as a legacy and heritage of Iran’s past for both present and future generations.