Hour 13:24

29 Jan 26

One of the key indicators of human development is life expectancy, which is closely tied to public health and hygiene. In the past two centuries, before the advancement of medical science, one of the main causes of premature death was the outbreak of epidemics, which struck different lands and claimed countless lives.

Cholera was one of the prominent diseases of that era and a sign of poverty, usually appearing after a period of famine. Until the second half of the 13th century AH / early 19th century CE, cholera was limmited to the Indian subcontinent, and there was little medical knowledge of it elsewhere. But with the expansion of maritime trade between countries during this period, the disease spread to other lands.

In the 13th century AH / 18th–19th century CE, seven global cholera pandemics occurred, and Iran, too, was struck by every one of them. Iran’s geographical position—between India, the Persian Gulf, Russia, and Mesopotamia—exposed it to cholera infection. In 1236 AH / 1820 CE, cholera entered Iran through the Persian Gulf; in 1244 AH / 1828 CE, and again in 1261–1263 AH / 1845–1846 CE, it entered through India and Afghanistan. In 1262 AH / 1845 CE alone, 12,000 people in Tehran died. The cholera epidemic of 1267–1269 AH / 1850–1852 CE claimed about 15,000 lives in Tehran. In 1284 AH / 1867 CE, cholera entered through Iraq, while in 1306 AH / 1888 CE and 1320 AH / 1902 CE, cholera spread into Iran again through Iraq and the Persian Gulf. Some sources also report that in 1286 AH / 1869 CE, after a famine, cholera spread in Tehran via a caravan returning from eastern Iran and the Indian border, with no preventive or precautionary measures taken.

Although neglect of public health was the main reason for the spread of such epidemics, Qajar kings and local rulers played an indirect role in worsening their effect. When cholera broke out, rulers typically fled, hid the truth and deceived the public; abandoning the people in danger. Officials, fearing road closures, did not notify neighboring countries of outbreaks. They also opposed quarantine, which required stockpiling grains and other costly provisions. For example, in the memoirs of Jules Richard, we find an account of the cholera of 1262 AH / 1846 CE. He relates how the Shah suddenly fled from the Niavaran summer palace and gardens to the northern mountains of Shemiran. This story is one of the key historical anecdotes tied to the Niavaran Palace. Such monuments are vessels of historical memory. This is not unique to Iran: across the world, palaces and gardens appear in historical records interwoven with cautionary tales that immortalize the memory of past calamities.

The tale of cholera in the Jahan-Nama gardens and Niavaran estate is told through the eyes of a famous Frenchman of the Qajar period who lived in Iran and was well known among both elites and commoners: Jules Richard (1816– ). He was later known as Richard Khan and, after converting to Islam, as Mirza Reza Khan. He became the first French teacher at the Dar al-Fonun school, where many leading Qajar statesmen learned the language from him. His name appears frequently in history books, newspapers, and memoirs of the era. He first came to Tehran during the reign of Mohammad Shah, intending to travel, but seeing opportunities for ambition and wealth, he stayed. After converting to Islam, he became a teacher at Dar al-Fonun under Naser al-Din Shah.

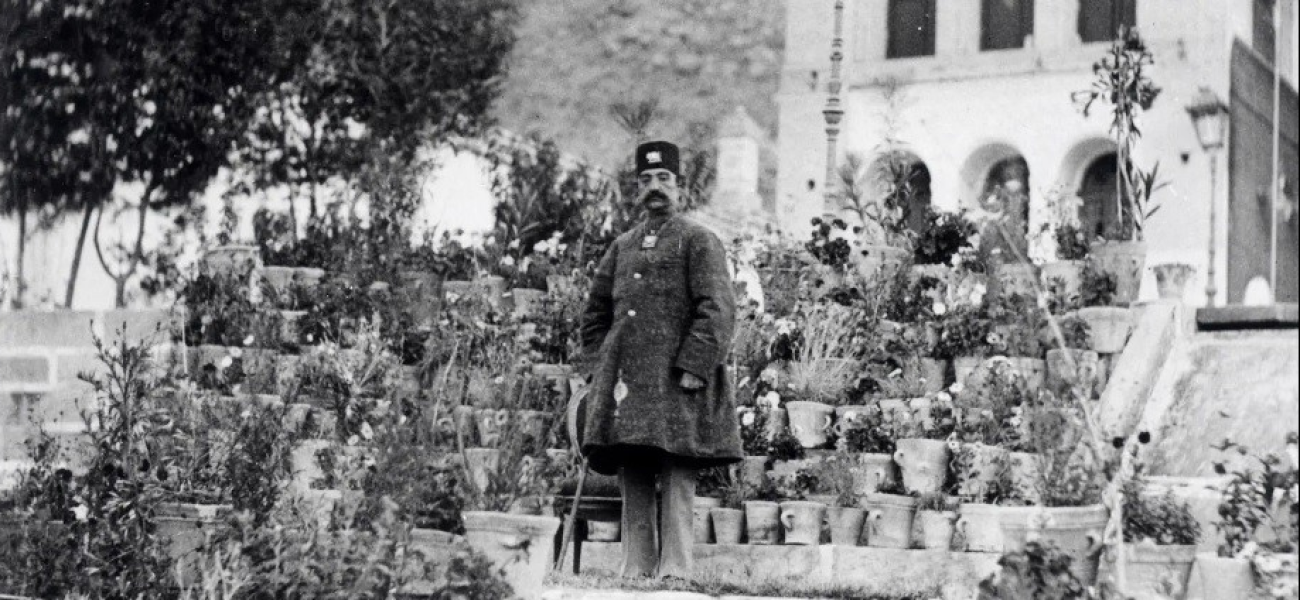

Caption: Portrait attributed to Jules Richard

One of the events he recounts is the cholera epidemic of 1262 AH / 1846 CE. At the time, he had brought some paper hot-air balloons to Tehran, similar to today’s red “wish lanterns” of Chinese tradition. The coincidence of their launch with the outbreak of cholera led common people to blame him, believing the balloons had provoked divine wrath for it is intervening with God’s will. He begins his account with his meeting with Mohammad Shah on January 28, 1846 (1262 AH) at the Niavaran summer palace:

“On the 28th of January [1846 CE / 1262 AH], at my meeting with the Shah, his first question was: ‘So! Did you bring me this balloon?’ I replied: ‘The large balloons that carry a man into the air are very expensive—at least a thousand tomans each—and bringing and operating them in Iran is extremely difficult. Instead, I have brought special paper for making sky lanterns.’ The Shah was delighted and said: ‘Very well, those small balloons you make for me will be enough.’

On July 21, when the Shah was in Niavaran, he summoned me to launch a lantern. For the event, a grand fireworks display was prepared. The balloon rose so high that it disappeared from sight; later I heard it landed in a village three farsakhs (about 18 km) away, where the frightened villagers fired their rifles at it. That night the Shah sent me a feast enough to feed ten people, along with a shawl as a gift.

On July 24, 1848 (22 Sha‘ban 1264 AH), when I came to Niavaran, the Shah had already fled into the mountains because of the cholera breakout. I heard some malcontents told the commoners that this cholera was caused by the balloons, but sensible people knew such talk was nonsense. On July 31, I counted 120 cholera victims being carried to the cemetery from the street where my residence was located, sometimes two or three piled in a single coffin. On August 4, I myself contracted cholera. No one would approach the sick. But thanks to the care of ‘Madame Abbas’ (a Frenchwoman who had converted to Islam and lived in Iran), though I hovered several times near death, I eventually recovered after eight or nine days.”

During the reign of Naser al-Din Shah, Mohammad Shah’s successor, flight from Tehran and Shemiran during cholera outbreaks became customary. The Shahrestanak Palace, once a royal hunting lodge, was turned into a refuge for the Shah and his courtiers in times of epidemic. Unlike the Niavaran palace, it was hidden in the mountains, inaccessible to the public and guarded by troops, making it the safest place for the ruler to escape the disease. Meanwhile, ordinary people died in groups, with no mountain palace, no army of guards, and no European doctors or nurses to save them.

Caption: Naser al-Din Shah taking refuge in Shahrstanak Palace during the cholera epidemic in Tehran and Shemiran (1271 AH / 1854 CE).

The newspaper Mellati wrote on 20 Jumada al-Awwal 1285 AH:

“Before this illness, the people hoped the royal court would safeguard both nation and state, for everyone depends on the court. Therefore its members should be capable of handling great affairs with foresight. Yet in this calamity, the opposite has proven to be true: the court dispersed, necessary duties were delayed, laws and regulations essential for the stability of state and nation were suspended, and the people were cast into poverty and misery.”