Hour 10:10

17 Jul 25

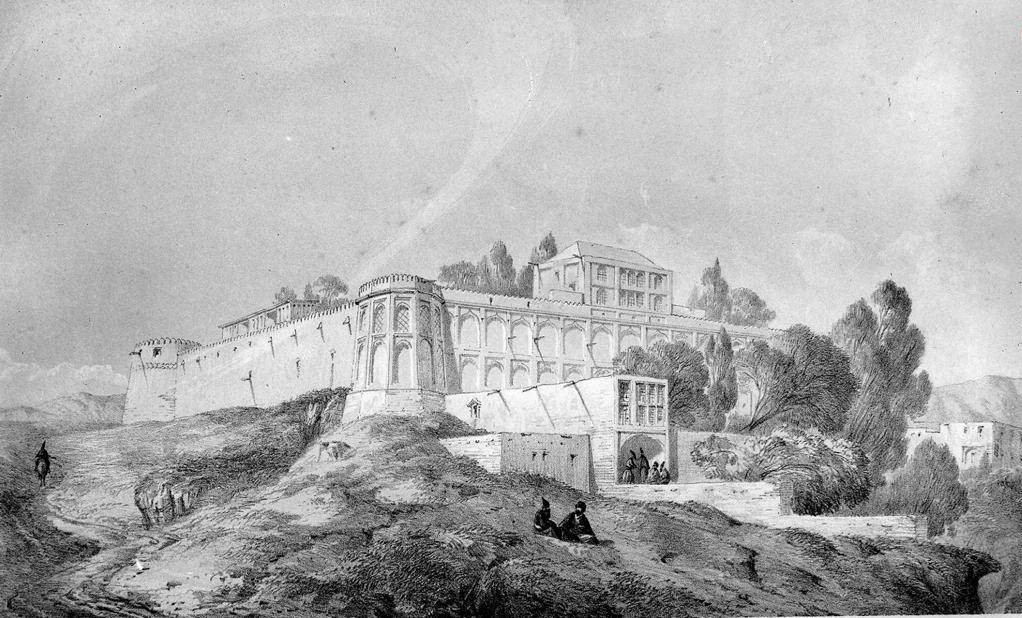

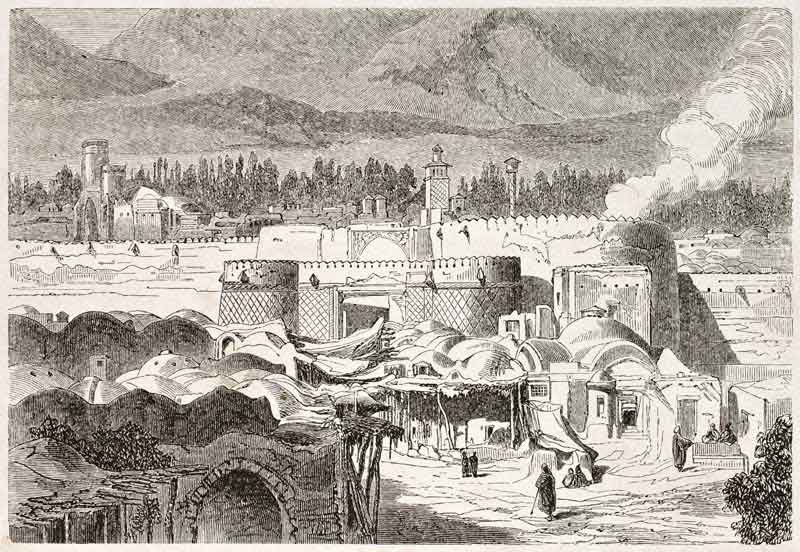

Tehran was a small settlement, surrounded by a wall dating back to the Safavid era, located near one of the oldest human settlements — the ancient city of Rey. It had gardens and recreational areas that began just outside its towers and walls, alongside the surrounding moat, stretching as far as the eye could see and the mind could imagine.

This dreamy land was the perfect place for travelers and passersby to relax without having to pay for it. Its pleasant weather and beautiful scenery left unforgettable memories for those who would rest under its plane trees. Tehran’s native birds — from the colorful parrots of Shemiran to the famous starlings of the city — watched over the people going about their day from the treetops, while high above them, kestrels (a kind of native hawk) with their reddish-brown chests and speckled bodies spread their wings, displaying their authority over the skies. One could enjoy the generous hospitality of the people of Tehran without spending a penny— picking fruits from gardens and vegetable fields and enjoying it as they stroll, experiencing firsthand the legendary Iranian hospitality that still amazes visitors to this day.

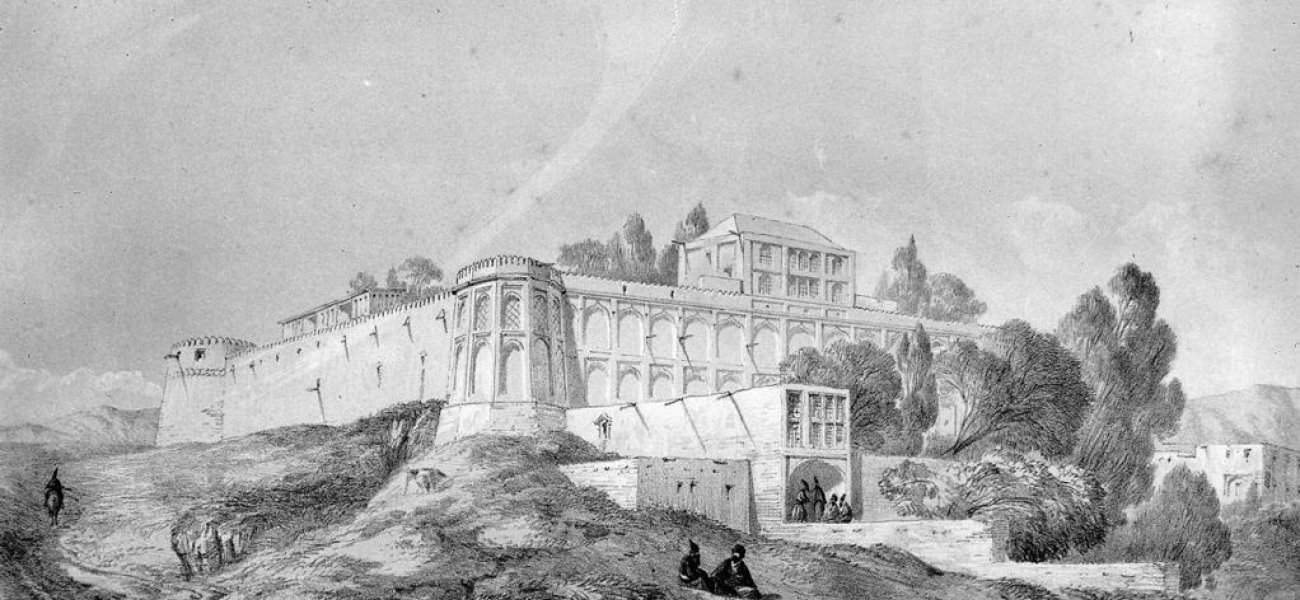

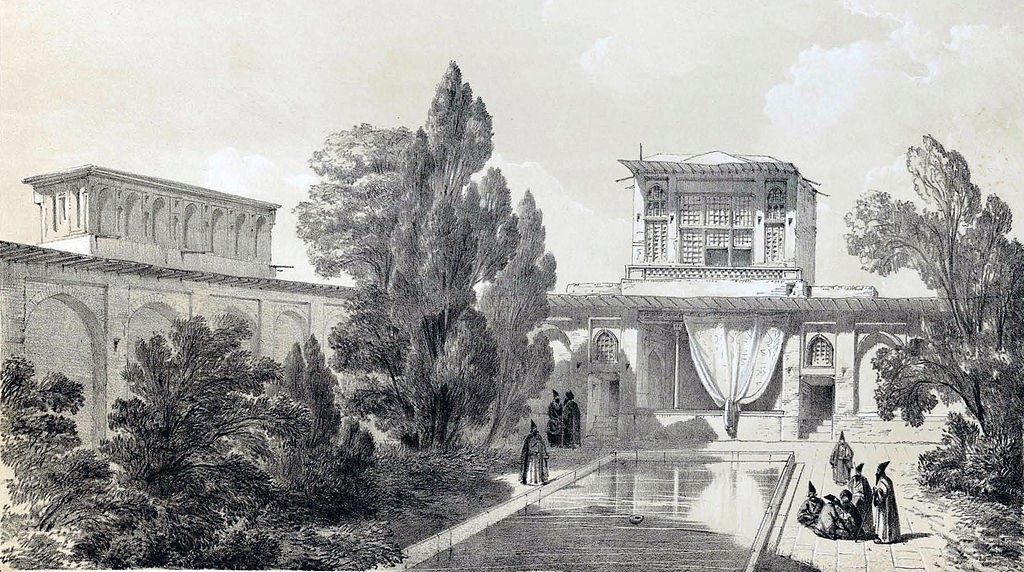

- Barout-khane, by Eugène Flandin

Above these gardens and fields lay the charming region of Shemiran, which, although largely occupied by palaces of kings, courtiers, influential figures, and foreign embassies, was still accessible to and enjoyed by ordinary people

As soon as the weather got warm, they would head to Shemiran, Tajrish, and the shrine of Imamzadeh Saleh. Some even camped for the entire hot season beside the estates of the wealthy, living with their families in tents. The aristocrats of Shemiran, true to the hospitable spirit of Iranians, would open their homes to these tent neighbors, offering them cool water from their qanats and sharing their food.

The people of Tehran, regardless of which part of the city they were from, lived like one big family, sharing whatever they had — little or much — with one another. It was customary that anyone about to eat would first look around in order to find someone to invite to share the meal with, for as old Tehranis would say: "Food doesn't taste good when eaten alone."

Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar, originally from the northern regions of Iran, Astarabad (modern-day Gorgan), would often stop in this pleasant settlement during his military campaigns to different parts of the country.

He would go to Shemiran to soothe his soul with memories of his homeland. A devout man, he would visit the shrines in Rey and Tehran and would sit on the bare ground, eating and talking with the people. Perhaps this was what sparked the idea of declaring Tehran the capital in his mind.

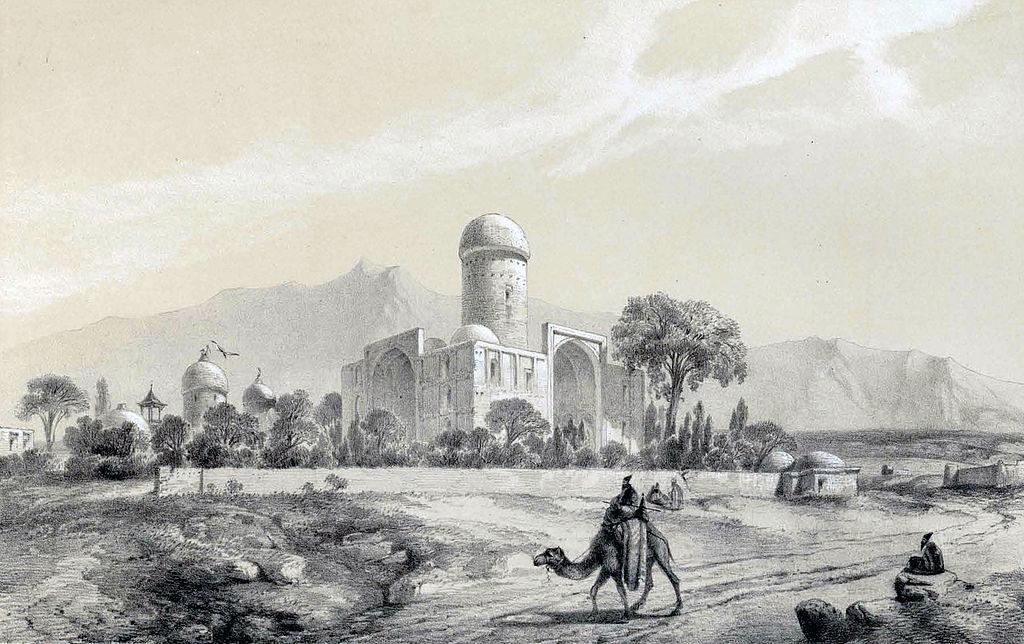

Tehran was located in the centre of Iran, far from the country's then volatile borders, close to Astarabad (Gorgan), and shielded by the towering Alborz Mountains. It was not like Shiraz or Kerman, which evoked memories of the Zand dynasty, nor like Khorasan, which recalled the Afsharids, nor like Isfahan, which were reminiscent of the Safavids. It was a small, peaceful settlement near the ancient city of Rey — whose former glory remained only in the form of religious shrines such as that of Hazrat Abdol Azim Hassani (Shah Abdol Azim).

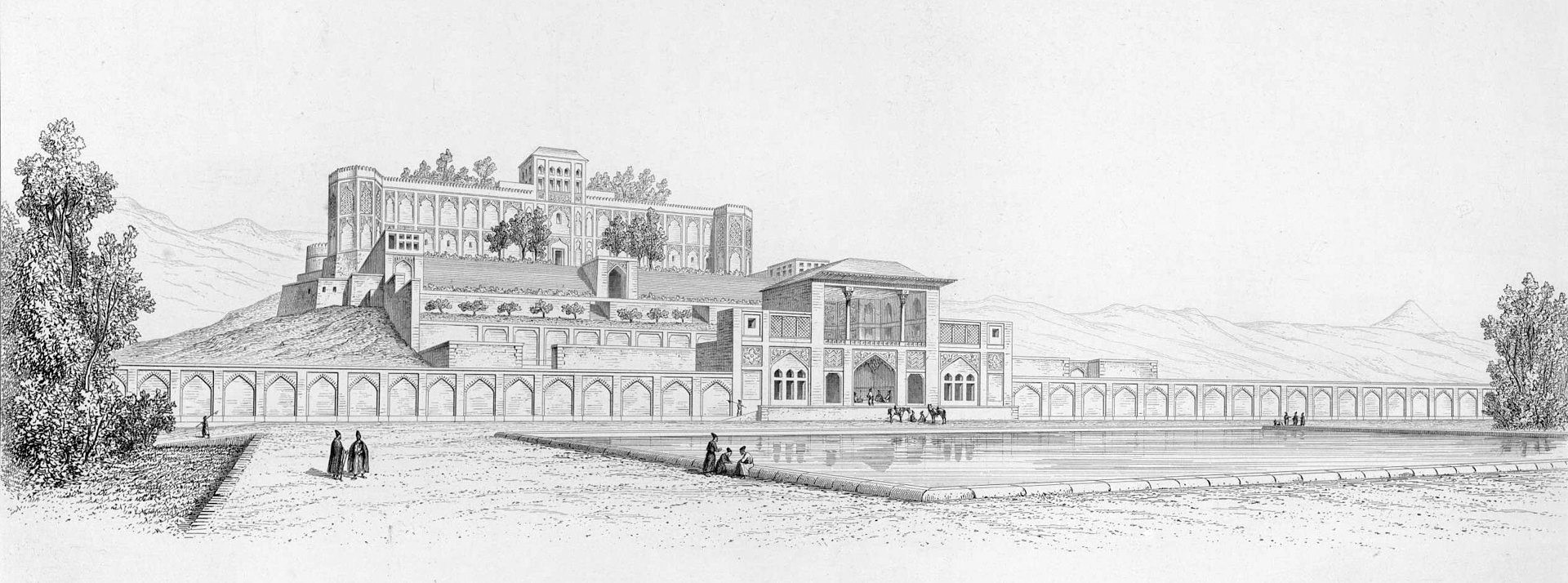

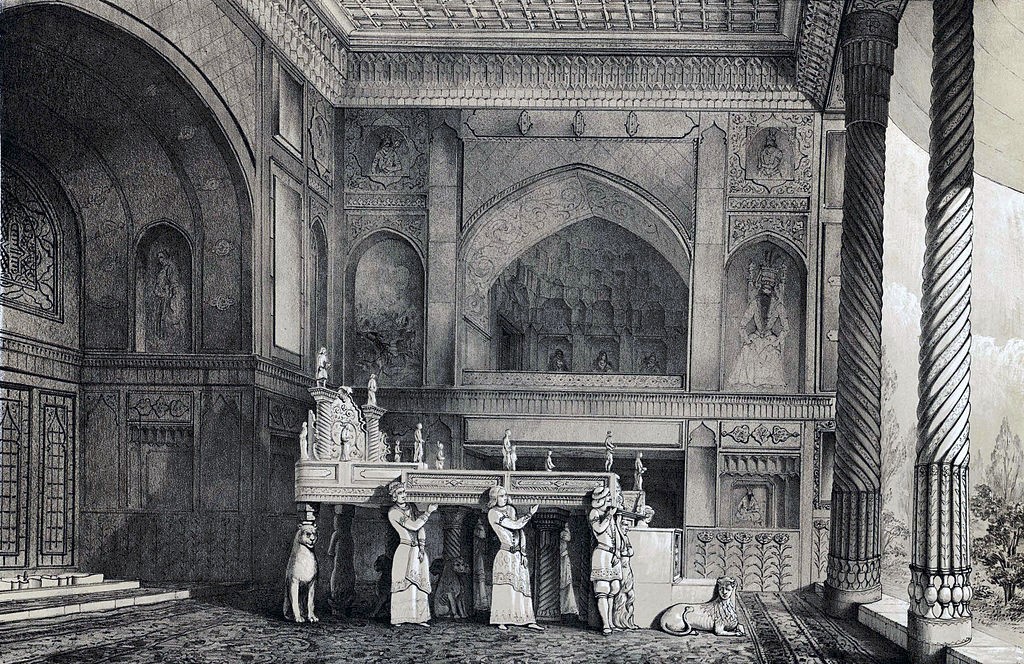

Agha Mohammad Khan made Tehran the capital of Iran, ascended the throne, and crowned himself king, declaring the structures which had remained from the Safavid era in Chaharbagh and Chenarestan Abbasi (now the Golestan Palace complex) as his royal seat. His successors gradually added to this complex, much of which still stands today and is visited by tourists.

During the reign of Naser al-Din Shah Qajar, the only major changes to Tehran’s physical form were, first, the city’s expansion through pushing the walls and moats outward — increasing its area from 12 to 24 square kilometers — and second, the introduction of Western lifestyles and practices through Iranian students sent abroad to study new sciences and technologies. These returning students, mostly sons of aristocrats, brought along with themselves the cultural habits of the Europeans which would later spread throughout the country. This also led to the fusion of European and Iranian architectural styles in governmental and royal buildings, many of which were designed—and at times even funded—by these returning students. They recounted the wonders of Western life and progress to the court, sparking curiosity and desire among the king and his courtiers to see the West for themselves.

So great was this intrigue that they spared no expense, granting significant concessions to Western companies in hopes of turning tales into reality. Eventually, the Qajar king, Naser al-Din Shah, managed to travel to Europe three times — in 1873, 1878, and 1889. His first trip, meant to meet Queen Victoria in London, was also the first time in history that a Persian king had visited a Christian European country. Interestingly, Queen Victoria, to honor Persian hospitality customs, had ordered for a traditional Persian bath to be built within her palace specifically for the Shah. Lord Sydney, a British politician and royal court minister of the time, inspected the bath before the Shah’s arrival to ensure everything was up to standard. What the Shah brought back from Europe was Western lifestyle and even architecture.

With the king and his courtiers now exposed to Europe, Tehran began to change— from its buildings to the streets, the shops, and even the clothing and appearance of its people. This was when Iran stepped into the modern age — a transition that was accelerated by the Constitutional Revolution and, eventually, the fall of the Qajar dynasty and rise of the Pahlavi dynasty. The fruit-bearing trees of Tehran's traditional gardens — symbols of Eastern living and poetic Iranian life — were gradually cleared to make way for tall buildings.

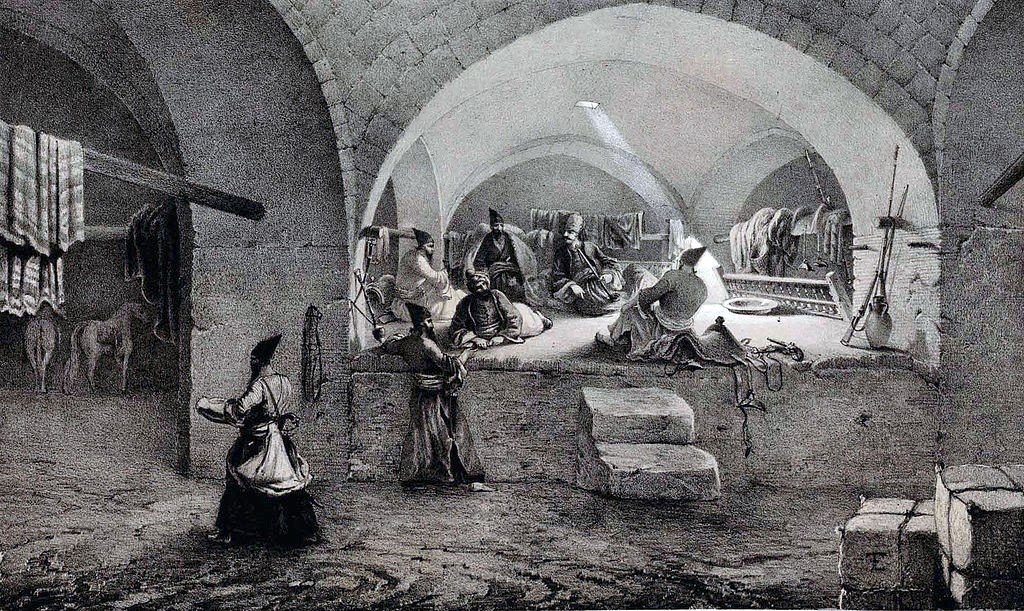

Furthermore, the capital’s coffeehouses, once vibrant cultural hubs where people gathered to rest from daily work, engage in business, exchange proverbs and folk stories, and enjoy entertainments such as poetry readings and epic storytelling, were replaced by cafés, lacking any unique Iranian cultural identity — indistinguishable from those in any other part of the world. These traditional coffeehouses, open from dawn until after all other shops had closed, featured lush garden areas for summer and spring gatherings and were decorated with unforgettable murals — the kind now recognized in the art world as Qahveh-khaneh painting, a unique genre in Iranian art history.