Hour 10:06

07 Sep 25

Niavaran is a summer retreat neighbourhood with a pleasant climate located in the northeast of Tehran, in the Shemiran district, on the southern slopes of the Alborz mountain range.

Its streets are steep, tree-lined, and lush, and from the olden days, crystal-clear water has always flowed in its streams and in its qanats.

The name “Niavaran” is derived from these springs—“Na” or “Nia” means “water.” This is evident in how Iranians today refer to the scent of moisture as the “smell of Na.” Another example of “Nia” meaning water is in the name of the city “Niasar,” which translates to “source of the spring.”

The clear and abundant spring water of Niavaran cascades dreamily down from the towering mountains on the north, mixing the fine water with the scent of flowers and greenery, caressing one’s cheeks and refreshing the soul. These sparkling streams that run through gardens and along the streets bring joy and satisfaction to all who pass. It is these springs that have made Niavaran what it is—from the Jamshidieh or Mansouri spring at the end of Jamshidieh Park to the spring located in the Niavaran Cultural-Historical Complex, as well as the Yourd and Piyazchal springs in Darabad.

Beyond these charming springs, what truly keeps Niavaran alive is its ancient qanats. Due to the unique geography of Shemiran and Tehran, situated on the steep southern slopes of the Alborz range, the early inhabitants used qanat technology to water the lands downhill—even to the furthest southern reaches of the region. If this mountain water had merely flowed on the surface, much of it would have been lost to evaporation or contamination.

Historically, the wealthy and affluent built summer homes and gardens in Niavaran to escape the heat of summer. One can still imagine the laughter of children beneath the trees and the cheerful voices of the families who would come from near and far to enjoy the cool shade of Niavaran’s trees.

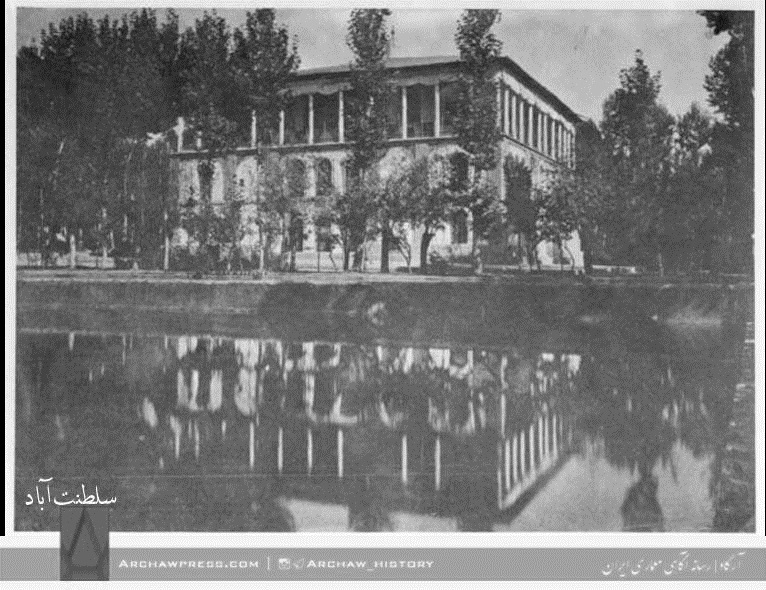

During the Qajar era, Fath-Ali Shah ordered a garden to be built for him in this area. His successor, Mohammad Shah, added buildings to the garden. However, it was Naser al-Din Shah who, early in his reign and under the supervision of Haj Ali Khan Hajeb-od-Dowleh, constructed a magnificent palace in the garden. This palace, overlooking a vast plain below with a panoramic view of all Shemiran and Tehran, was named “Jahan-Nama-ye Niavaran” (Niavaran's World Viewer), meaning the whole world could be observed from it. It was built with astonishing architecture—water was flow from the lower levels to the top, where it gushed from the central fountain of three upper-level pools, creating a heavenly atmosphere. Given all this, it never became known why the building was later demolished and replaced with the Sahebqaraniyeh Palace, though the grounds and layout of the Niavaran garden were left unchanged.

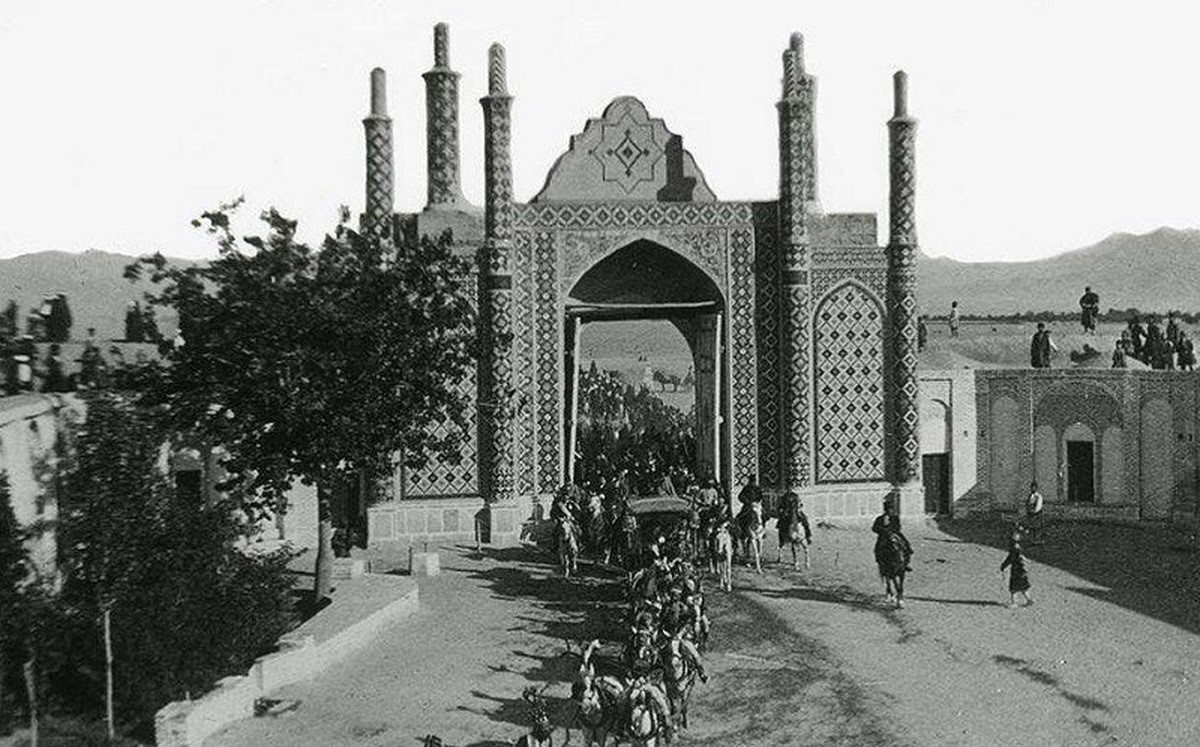

Gradually, roads were constructed to connect the Niavaran garden to Tehran, passing through the Saltanat-Abad garden and reaching one of the northern gates of Tehran, known as the “Darvazeh Shemiran” (Shemiran Gate).

At the time, this road was known as Saltanat-Abad Street, but today it is called Pasdaran Street.

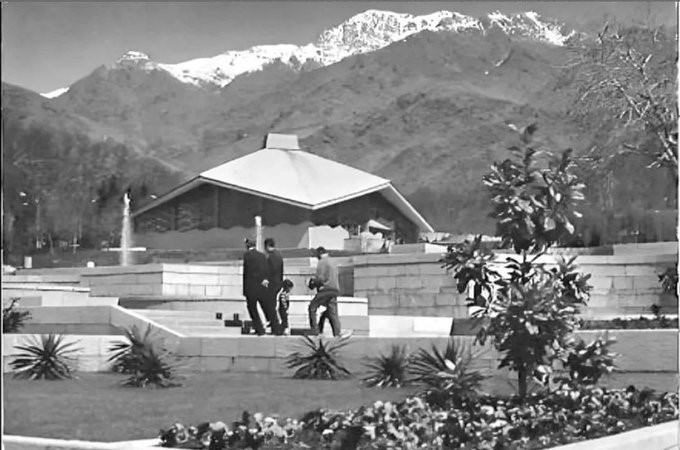

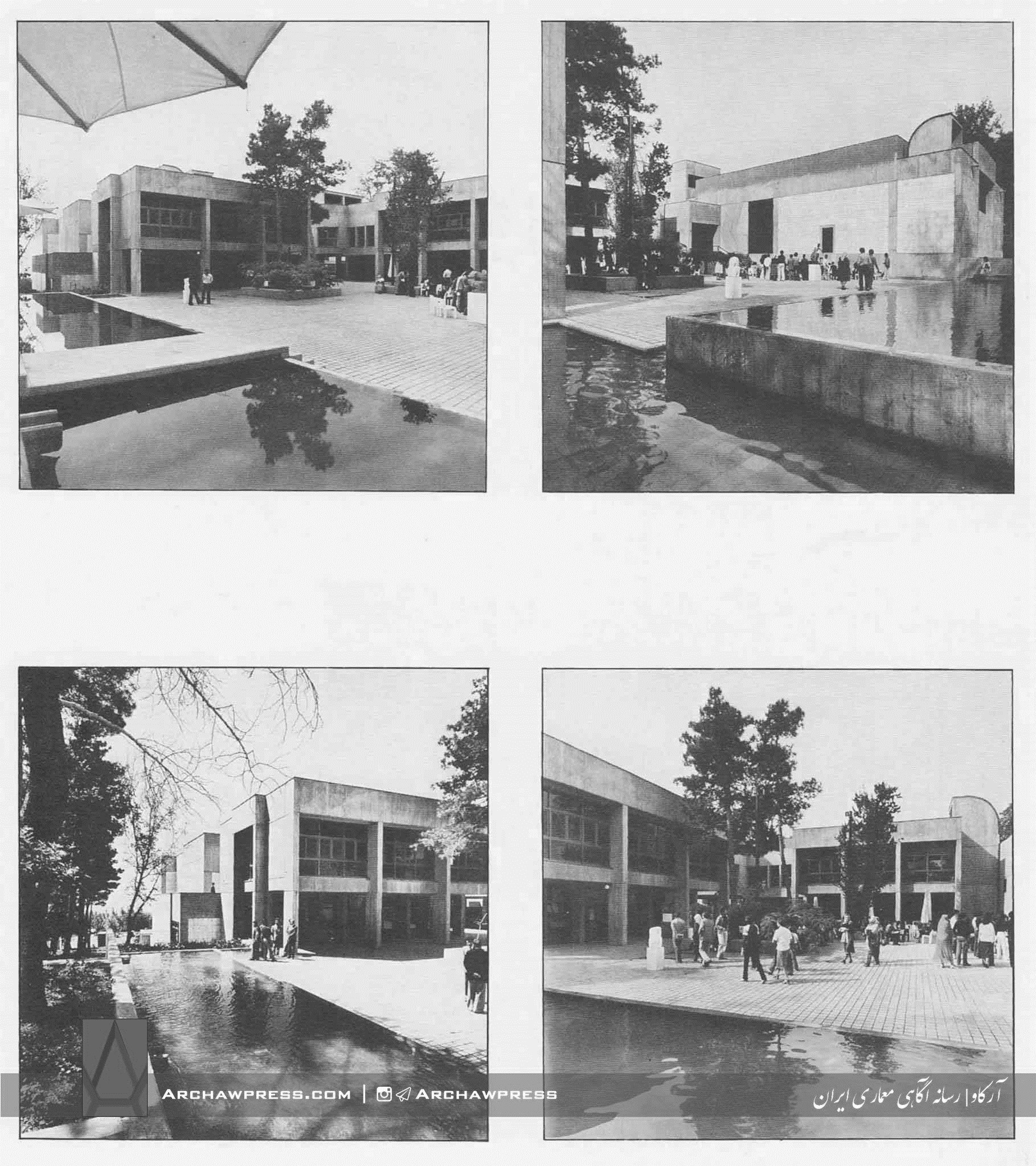

Later on, a portion of the Niavaran garden located below the Sahebqaraniyeh Palace was transformed into a public park named “Niavaran Park.”

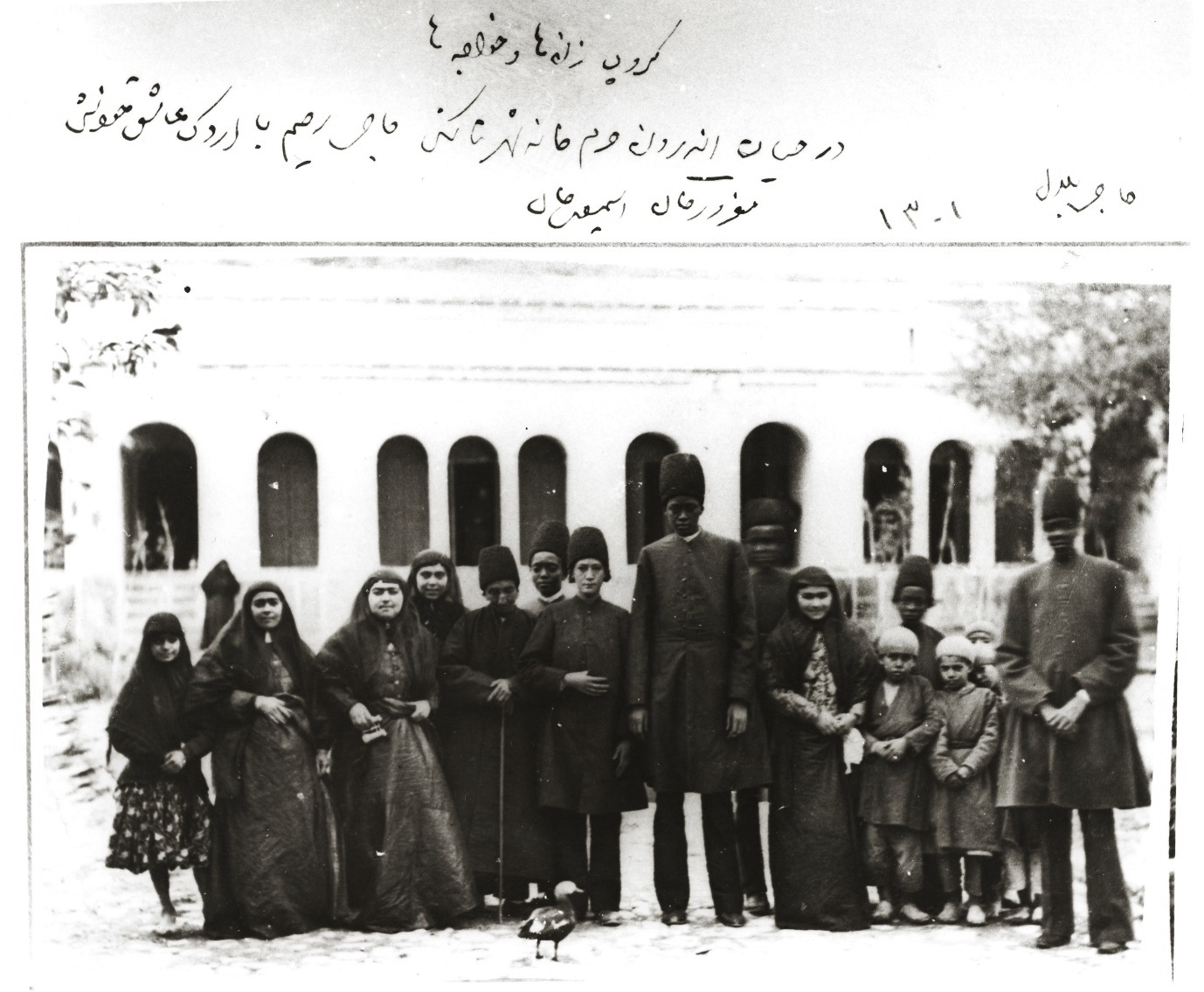

Beyond the Niavaran garden, one of the largest estates in the area once belonged to Aziz Khan, a eunuch in the Qajar harem. The current location of the Niavaran Cultural Centre and its vast surrounding garden, east of the Hesar-e Bouali neighbourhood, was once known as the “Aziz Khan Garden” and was his personal property. In the past, owning male and female servants (gholams and kanizes) was common practice.

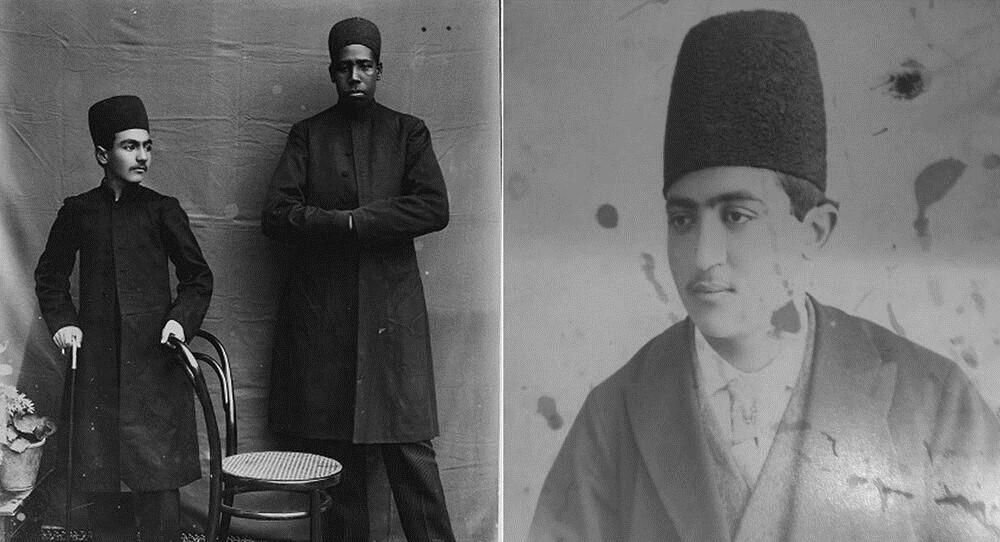

But these servants were quite different from the stereotypes (physically unappealing and intellectually deficient) we might imagine today—many were intelligent and skilled in arts such as music, singing, and other talents. So much so that the names or memories of these servants are still remembered by people or mentioned in books. Some were even sent as royal gifts to other courts. Many male servants were well-versed in literature, storytelling, and conversation, while female servants were skilled in childcare and serving noblewomen. Aziz Khan, a court eunuch close with Mirza Ali Asghar Khan Atabak known as Amīn al-Sultān (the grand vizier), became one of the wealthiest and most influential landowners of the Qajar era. Castrated in childhood, he lived in Naser al-Din Shah’s harem.

When Amīn al-Sultān noticed Aziz Khan’s intelligence, he recruited him to secretly report on the internal affairs of the harem and Shah’s relationship with women. Once the Shah discovered that sensitive information was leaking to Amīn al-Sultān through Aziz Khan, he expelled him from the harem and handed him over to Amīn al-Sultān. Over time, as all matters of state were handled by Amīn al-Sultān, people would go through Aziz Khan as a middleman to get things done, always giving him a share of the deal or bribe in return. Many of the elites, knowing his closeness to the Amīn al-Sultān, would gift him money and property, so it was not long before he came in possession of wealth and influence. Meaning that he owned the finest and most desirable properties around Tehran at the time (which today are a part of Tehran and Shemiran), the best jewels, the most exquisite carpets, the most luxurious furniture, several grand mansions, and a vast park. Aziz Khan had no wife or children due to his eunuch status. Upon his death, by his will, his wealth was donated to charity. His private garden and residence first became a sanatorium for tuberculosis patients and were later turned into the Niavaran Cultural Centre. An educated and book-loving man, Aziz Khan had built a significant private library, which after his death—per his own wishes—was donated to the National Library of Iran and became one of its first foundational collections. The remainder of his wealth was also used for charitable purposes.

These are only glimpses into the rich historical identity of Niavaran. Niavaran holds countless stories in its heart. Every alley and street tell tales of the bittersweet moments of past lives—of unions and separations, gains and losses. And yet, anyone who walks through Niavaran feels that, despite its ancient history, it remains young and vibrant. Perhaps this is the secret of its flowing springs—like a “Fountain of Youth,” they bestow eternal life and vitality upon Niavaran.